Tags

1970s, 1973, Avon Books, Barry Malzberg, first contact, held hostage, New Wave SF, prison planet, psychological, science fiction

Here we are: in the enclosure. It has been some two years and four months since we were placed here (I have fully assimilated a sense of their chronology) and now, past the initial riots and educative tortures, things are comfortable.

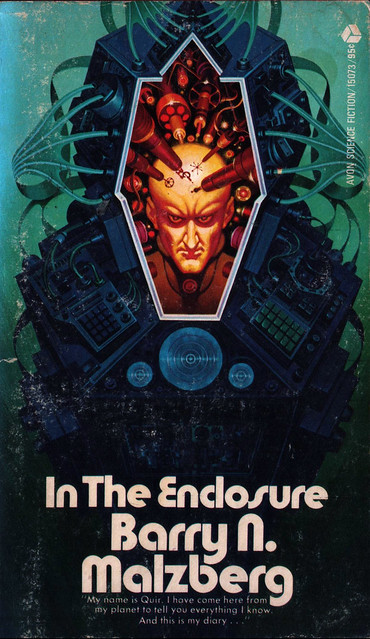

So, Barry Malzberg: for a decade—1968 to 1978—he was incredibly prolific in the SF field, writing some twenty novels and over a hundred shorter works, on top of articles and genre criticism and the like. His output slowed and stopped altogether within a few years, and disillusion with the genre of the ’80s set in, though he continued to publish short fiction to this day. I wouldn’t be surprised if a large segment of readers knew him from last year’s SFWA drama, despite the critical acclaim his works have earned over the years. Joachim at Science Fiction Ruminations speaks highly of Malzberg, and has done much to promote his work over the years.

Quir is one-hundred and fifty-eighth of a crew of 248, sent to Earth to make first contact and impart knowledge from the stars. When they met the aliens (humans), Quir and his crew are shuffled into the formless enclosure and get tortured for information. Luckily, Quir’s masters back at his home planet had wiped the memories of the entire crew; instead, their minds are packed with technical information—chemistry, geology, mathematics—and they are conditioned not to lie, to be subservient to such forceful questioning. Now, it’s been over two years since they landed, and they remain in the enclosure: the alien (human) “therapists” promise that the political situation is changing given their compliance in providing information, but the sessions continue: a dull existence of answering questions related to one’s profession.

Quir is quite comfortable in the enclosure, and recoils when a higher-ranked compatriot named Plotar seeks his aid as part of an elaborate escape attempt. Turning in his superior, Quir is racked with guilt… and a desire not to be seen as a coward. In response, he begins to form his own escape plan, albeit a less-flashy plan he makes up overnight after attracting some half-hearted followers. And so, here they are, in the enclosure: Quir desperate to prove his worth by breaking out, leading the group to their abandoned ship, to fly it to a ticker-tape parade back home.

I knew going in that Malzberg’s fiction is most often metafictional and psychological, using science fiction as a method to explore deep psychological concepts, a backdrop to explore social constructs, and a means of entering philosophical debate. In The Enclosure didn’t disappoint on those fronts. Naturally, it’s an exploration of confinement and control—not just the confinement of the enclosure, but of the hierarchical system the aliens come from. It stems from that core conceit, and Malzberg’s sardonic black humor that becomes depressing well before the final reveal twists the knife: perhaps you’re not cynical enough to believe that humanity’s first instinct upon receiving visitors won’t be to throw them in prison and torture them for information, without proper trial and in flagrant disregard for “innocence before proven guilt before a trial of their peers,” to which I respond “Hello, Guantanamo!”

It’s fitting that, with this strict hierarchical system, only those ranked below Quir will follow his half-baked plan, even as Quir rebels against the system—rebels against Plotar, at least, in resentment for Plotar’s higher rank as the master of rituals. It’s also fitting that Quir’s sexual politics are neolithic. If the humans treat the aliens as cattle, Quir treats “females” as objects, walking into a hallway and having his way with one as the need arises. (Quir is no hero here; the piteous and sympathetic victim sobs out “Bastard!” as Quir walks back to his room. And Quir’s mirror image, the most able person of the would-be escapees, the one with the most memory of their home planet and purpose, is the woman Nala.) There’s also a Philip K. Dickian questioning of reality: what is real? Is it what we’re told, what we hope, or what we know—even though any of these may be a construct imprinted on our mind consisting of lies? The aliens never know what occurs outside the enclosure, whether their gifts are put to good use, if the geopolitical situation really will change and lead to their freedom… and maybe they’d rather not know the reason they were sent to Earth to regurgitate information for those who restrain and torture them, their minds wiped clean with promise of glorious memories upon their return home.

I’m also struck by Quir’s presentation as a self-serving dunderhead with an over-inflated ego; after turning in Plotar to the aliens, an attempt to keep the status quo where he is rewarded with old magazines for giving evasive answers to geology questions, he becomes rankled by accusations of treason and cowardice. He crafts an elaborate image of himself that none of the others seem to share, telling us (and maybe himself) of his “noble” intentions which are clearly self-serving. He becomes deluded by this glamour, dreaming of making heroic speeches and being elected leader once the group flees and reaches their ship, enjoying a heroic kiss with a woman as the crew cheers in the background. Quir’s hopes are as melodramatic as the situation in the enclosure is depressing, and it makes for sharp and brutal contrast. Malzberg’s prose helps out as well; it comes across as monotonous and facile, but to me it amplified everything Malzberg was saying in this novel.

In The Enclosure is the kind of smart and bitterly sardonic novel that uses the framework of SF to ask deep and disturbing questions. Calling it “depressing” and “disturbing” may come across as a knock against the novel, but that’s not my intent; it’s cut from the same cloth as Disch’s classic Camp Concentration, using its black humor for added bite. It’s an intellectually stimulating read that asks some hard-hitting questions, unsettling in the accuracy and veracity of its content. I realize that not everyone is willing to read a book that isn’t fun, lighthearted fluff, even though there are uncomfortable questions worth asking (and for most of those, it’s also worth sitting in awkward silence as you listen to the also-uncomfortable answers). Fans more tolerant of serious, unsettling themes—the blackest of black comedy, almost gallows’ humor—should consider picking up a copy. It’s a thinker, and a solid one at that.

Book Details

Title: In The Enclosure

Editor: Barry Malzberg

First Published Date: 1973

What I Read: 1973 Avon paperback

Price I Paid: $2.50

MSRP: hard copy OOP / $2.99 ebook

ISBN/ASIN: B00H6SOHNK

I know Joachim Boas has done much to promote Barry Malzberg’s work on his blog! It’s because of him I’ve read any of his stuff.Since this time last year I’ve read “Beyond Apollo” and “Universe Day”.Unfortunately,so far,I’ve found them far from exceptional.He’s recommended “The Gamesman” to be my next read of his.I hope I find it better.

I know there must be something in him.Perhaps I don’t like his strait-laced,more traditional themes he builds his visionary stuff from.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Not sure all of his stuff is build out of “strait-laced” SF topics — for example, Guernica Night…. Or, Chorale (which I have not yet read but plan to).

LikeLike

*built

But yes, I think that is what bothers people so much about his work — the fact that it subverts what they might expect to be standard. And that is what is appealing! Although, the subject of In the Enclosure isn’t exactly a standard SF theme either.

LikeLike

I like iconoclastic stuff.Gone I should think are the days when sf glorified astronauts.That should make his stuff very appealing to me then…..should do.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No,I don’t suppose it is,but so far,what I’ve read has relied on old fashioned astronaut characters.

LikeLike

Weren’t those old fashioned astronauts cutting edge at one point? Like when Malzberg was writing those novels back in the 70s? That historical context contemporary with the Apollo program fascinates me, which makes me want to read his other works like THE FALLING ASTRONAUTS.

LikeLike

I don’t know,probably,but I think Brian Aldiss probably gets it right in his history of sf,”Trillion Year Spree”,where he says that,”the cherished dream of NASA became,in Malzberg’s skillful hands,the stuff of existential nightmare,as novels like “Beyond Apollo” and “The Men Inside” demonstrated”.Wasn’t he seeking to deglamorise the romantic dream of the “bold” astronauts too?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you’re right, he definitely wrote a lot of works deconstructing NASA’s romantic appeal. On the one hand it’s an interesting contrast to so many earlier works in the genre (specifically 1950s), and nothing should be free of criticism. On the other hand, I’m still enough of an idealist to think manned space exploration is a noble pursuit.

LikeLike

Most of the best modern sf has portrayed space travel with a negative eye.It’s part of the tenophobic attitude that has changed sf and brought it to maturity.

LikeLike

I’m not sure what long term benefits space travel will have for Mankind,nor what effects it will have on the astronauts,but once again,Malzberg has the last word on it,I suppose.

LikeLike

I haven’t read nearly enough Malzberg, and this sounds ideal fodder for me. Many thanks for an insightful essay.

LikeLiked by 1 person

DO IT! (I have read 11 or so of his novels and a short story collection and I love them!)

LikeLike

Thanks, John. Curious what you would have to say about them 🙂

LikeLike

I read a few back in the day, when they were definitely ahead of the curve so far as the sf mainstream was concerned. I can recall being quite upset when Beyond Apollo turned out not to be about jolly adventures along the spaceways! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Malzberg has been a favorite. I’d encourage everyone to read his novels and short stories.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I had NO idea you were a fan! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Which of Malzberg’s works are your favorites?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Top Five Favorites::

Beyond Apollo

The Remaking Of Sigmund Freud

The Cross Of Fire

Herovit’s World

Down Here In The Dream Quarter(Short Stories)

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Hello, Guantanamo!” No kidding.

Guernica Nights (AND Disch’s The Genocides, too) will be coming up for me in 2016. I’m both leery and looking forward to it. I suspect he’s going to ruffle my feathers, but I hope it’s not worse than what I’m used to reading from that decade, and if it is, I hope there is some narrative justification that doesn’t have a better alternative.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, worst case scenario, blame Joachim 🙂 I’m kind of wondering if he will ruffle your feathers, if only because that’s the kind of author he seems like—certainly ruffled feathers with his novels criticizing the Apollo program— but having read a whopping one of his books I’m not really an authority here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Blame Joachim” sounds like a good slogan to me! 😉

Space pessimism doesn’t bother me. I like contrarian writers, but I’m afraid he’s going to come off as a sexist twit somewhere. Actually, I’m sure he will, I just hope the novel is worth the cringing I will probably do. If it’s slightly better than Dangerous Visions levels of sexism and does not exceed or match Heinlein levels of sexism, I won’t harp on it.

Omg… I need to make a spectrum…

LikeLiked by 1 person

There were some rather shocking comments in this one that I’d love to see you tear into… I’ve noticed that ’70s SF, even some of the great ones, is packed full of sexism. I have to wonder how much of that kind of misogyny was in response to the Women’s Lib movement and how much helped spark it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I should note that his main characters are anti-heroes through and through…. and yes, sexist antiheroes (which fits into his idea that this technological transformation also transforms and brutalizes man, i.e. they are now machines). But, a lot of the frustration with his work is due to his very unlikable main characters… which obviously, all sort of versions of the archetypal transformed “machine man.”

LikeLike

I should edit before I post — “are all sorts of permutations of the archetypal transformed…”

LikeLike

I have to agree—Quir was unlikable/obnoxious by intent as a protagonist. Despite his predicament, I didn’t feel connected to or sympathetic for him before he did sexist things. If a protag the author has painted as unlikable does something sexist, does that make the work/author sexist?

Though, talking about “lady editors” and judging them based on how attractive they were in swimsuits is pretty damn sexist…

LikeLike

Worded that way, it sounds a lot like Simon Ings’s Wolves, which I LOVED. Unfortunately, Malzberg’s reputation undermines that kind of statement. Forgiving the catalyzing event would be fine, but the resentment he blasted at critics afterward gives me pause.

LikeLike