Tags

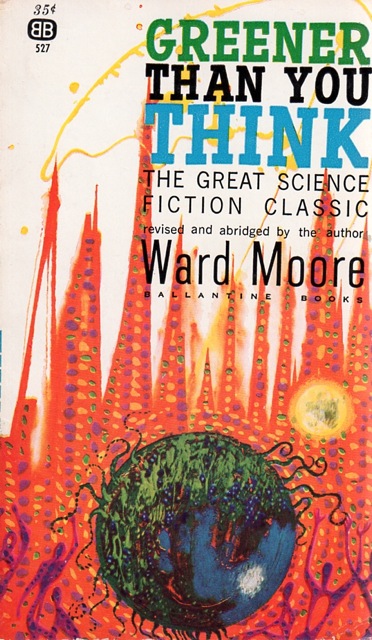

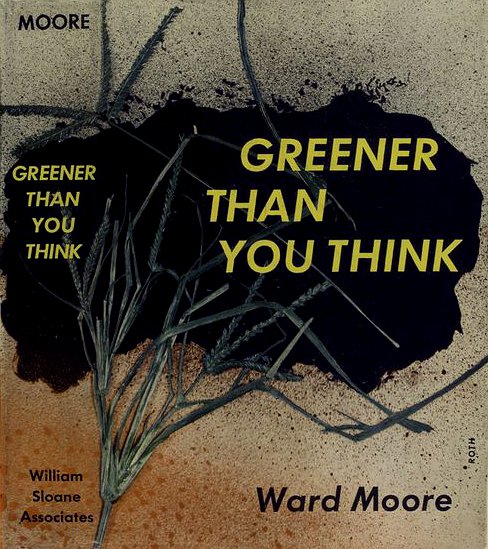

1940s, 1947, apocalyptic, Atomic Age!, Ballantine Books, Cold War, ecological, Richard Powers, science fiction, social satire, Ward Moore

Ward Moore is another in the legion of forgotten science fiction writers. Most productive in the 1950s, Moore was a mainstay of the early Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, but despite his popularity with readers and editor Anthony Boucher Moore’s SF output was not prolific, limited to some twenty stories. Of his half-dozen novels, the best remembered are alternate histories Bring the Jubilee (an early “Confederacy won the American Civil War” novel) and Joyleg (coauthored with the more famous Avram Davidson). Greener Than You Think was Moore’s first science fiction outing, following several Depression-era dramas. Despite a 1961 reprint, a 1985 British reprint in Crown’s “Classics of Modern Science Fiction” series, and a 2008 reprint by Wildside Press, Greener Than You Think remains forgotten.

Albert Weener, down on his luck salesman, makes the fortuitous choice to answer an ad in the newspaper. He finds himself employed by Josephine Spencer Francis, a scientist who’s discovered a magical growth formula to make any grasses flourish with increased rapidity, and who hopes to end world hunger by making the dust bowls bloom. Weener decides that it’s easier to sell the miracle tonic to suburban housewives hoping for a greener yard than it is governments or farmers, so he heads into town and applies it to a dying yard of Bermuda grass. Without realizing it, Weener’s set off a chain reaction; Josephine realized she sent Weener out too soon, having forgotten to include a crucial piece of the formula. When they return to the lawn the next day, the grass has erupted upward, and resists attempts by various mowers (and even a farmer with a scythe) to prune it.

The novel’s second and third acts begin like a ’50s b-movie: Watch the spread of the unkillable grass! The military is powerless against its foliage!—cue leftover World War II materiel driving around the city, tanks engulfed by grass, artillery lobbing futile shells at the sea of green. Weener narrates the grass’s spread as he progresses from role to role; he’s first hired as a newspaperman covering the various attempts to stop it, only to find his horrible articles ghost-written by better writers. Then he branches out as a business-owning capitalist, moving upward by pluck, luck, and fast thinking, eventually coming to dominate what is left of the ever-more-grass-covered world.

The novel’s place in time gives it the irony of satirizing and commenting on two eras at once. Moore clearly had memories of the Dust Bowl when he penned Greener Than You Think, of the drought and desertification of the ’30s that dominated his earlier works (such as 1942’s Breathe the Air Again). Meanwhile, the novel also reveals the changing dynamic in the post-War world, of the consumerism and suburban expansion that would come to dominate the 1950s and ’60s—after all, a big part of keeping up with the Joneses was the outward appearance of your house and lawn. One moment, Weener and Francis are harangued by a kangaroo court which foreshadows the worst of McCarthyism yet to come. Some chapters later, the military assaults the grass with “[t]he bludgeon which reduced the cities of Europe to mere shells,” first firebombing Los Angeles and then unleashing atomic bombs. A few later, the U.S. and Soviet Union are at war, fighting a petty conflict over petty reasons while the grass overtakes the Western U.S. and countless Soviet armies.

And the role of science in the gigantification of this grass stands out to me; some elements of the book remind me of the ’50s B-movies, namely Godzilla. Not just in the unstoppable monstrous force—here, vegetation, almost a parody of the giant bugs and lizards yet to come—but in it relays fears about science, the science and technology born from World War. Science in the ’40s is a double-edged sword; in one hand it brings vaccines and cheap energy, in the other it brings atomic death.

In that way the novel is a bitter reflection of human civilization, in a scathing manner often approaching absurdity. Moore keeps the novel on a level-headed progression, but he has a Swiftian sense of comedy, blending gallows humor with fantasy and the absurd; it never feels as blatantly over-the-top as, say, Vonnegut, but Moore is writing in a similar (but more cynical) vein. Take, for example, the petty human conflicts and woes that propagate along with the spread of the grass. Weener spends much of the book worried about his self-serving schemes to better his position, even as the grass overtakes the world; scientists and generals and citizens bicker about various plots to stop the grass, and even moreso about pointless minutia—the aforementioned court spends more time determining whether crude oil was poured on the grass and not to why the oil failed to kill it.

Moore’s prose is uniquely suited to this work; it’s very formal prose, though pseudo-intellectual, combining Weener’s purple journalistic prose with his inflated opinion of himself. It’s dense, but approachable, and comic in its own way. The dialogue is similarly surreal; the characters include: another of the paper’s reporters who speaks predominantly in silly accents, the newspaper’s belligerent and degrading boss who is the voice of reason in this work, the cynical Josephine Francis (well-spoken despite her utter lack of a formal education), an old warhorse general turned reluctant quartermaster, the general’s lazy son who’s turned into a traveling author part Hemingway and part Kerouac. The characters are not very deep, nor is there much development, but that manages to work to the novel’s benefit, playing into its satirical point.

I mentioned that Weener’s self-aggrandizing; he’s also self-serving. It’s through Weener that most of Moore’s satire comes out, along with most of his cynicism; as you progress through the novel you start to realize that Weener is nothing more than an opportunist, clawing his way further up the socio-economic ladder through shady and underhanded business deals, while he blames others for his misfortune and mistakes; this becomes more and more absurd as the novel progresses. When the grass has overrun half the world, Weener justifies himself as a philanthropist since he donates mass amounts of (now worthless) money to charitable causes. Rather than searching for a way to kill the grass, he becomes the stereotypical robber-baron, owning more money and resources than the world governments thanks to the necessity of his Consolidated Pemmican company—pemmican being a meat-paste which has become the diet staple of the world.

And when an anti-grass measure may be at hand, instead of saving the world, Weener puts Consolidated Pemmican’s importance first—owning more money than anyone else, along with the world’s entire food supply (in the form of pemmican), he holds out on the anti-grass cure until it’s overrun the planet… because he’s interested in finding a way to make pemmican out of the grass. Weener is a critical damnation of humanity, a dithering character who—along with the rest of the world leaders—decides that rather than band together to work for a cure, it’s simpler to make sad platitudes about the growing death toll and wait for someone else to stop the grass. His opinion changes like the wind, the only constant being that Albert Weener is an innocent bystander caught up in circumstances beyond his control. Moore’s opinion is best set up by his opening paragraph:

Neither the vegetation nor people in this book are entirely fictitious. But, reader, no person pictured here is you. With one exception. You, Sir, Miss, or Madam – whatever your country or station – are Albert Weener. As I am Albert Weener.

It took me a few chapters to decide that this was a good read, and by the bittersweet end I’d decided that Greener Than You Think is an outstanding, forgotten classic. It’s a no-holds-barred satire of humanity in conflict with itself, using the catastrophe of the grass to examine the human microcosm. Its place between World War II and the Cold War gives it leverage in its commentary, a distinct feeling of its place in time. As the first novel I read in 2013, it’s also the first great novel I read this year; it’s an impressive novel, and a shame it’s not more widely known. Since it’s available free on Project Gutenberg, as well as in hard copy from Wildside Press, it’s an easy book to find. And if you’re a science fiction reader, I recommend that you do.

This review is part of Vintage Sci-Fi Month; not that I needed an excuse to read vintage science fiction.

Based on what you say, I’ve just ordered it!

The only Ward Moore book I’ve read is Bring the Jubilee, which I liked well enough but wouldn’t rate as highly as many people seem to.

Actually, I thought initially you would be sure to mention Norman Borlaug and the Green Revolution, ( http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_Revolution ) referring as it does to the development of substantially faster growing, more productive cereal crops to help the developing world. Later in your review I was also reminded of corporations like Monsanto whose sterile gene-modified crops rely on new purchaes of their seed every year…

Finally, as the opposite of events in Greener Than You Think, you might care to read The Death of Grass by John Christopher, which is an English disaster novel (but a bit grimmer than Wyndham’s). It’s the story of a bunch of people fleeing impending famine in London and heading for a relative’s remote potato farm!

Massive spoilers in what I wrote here:

Happy New Year,

Mike

LikeLike

The connection between the Green Revolution completely slipped my mind, though I had planned on mentioning The Death of Grass, if only because they both look at a similar theme… I’ve meant to read that one for a long time, because of my love of catastrophe novels. I might have to go buy it to do a compare/contrast with Greener…

LikeLike

Wow, very little of this type of sci-fi has passed by my scrutiny and I’m delightly you’ve found it! Bonus: Project Gutenberg! This one’ll be downloaded to my Reader soon.

LikeLike

I read the Gutenberg version, and it was fine apart from some weird word amalgamations for compound nouns (was never really sure if it was just missing spaces, or if Ward Moore hated hyphenation).

Glad I found something right up your alley! I await your review.

LikeLike

Nice review! This is definitely one of the key, post-Hiroshima end of the world satires that came out in the late in the late 40’s. I think Moore’s book is better and funnier than some other competitors of that time, like Pat Frank’s Mr. Adam and Aldus Huxley’s Ape and Essence.

LikeLike

Pingback: 2013 In Review | Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased

Pingback: “Lot” and “Lot’s Daughter” – Ward Moore | Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased

Pingback: Bring the Jubilee – Ward Moore | Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased