Tags

1940s, 1950s, 1955, anthology/collection, Ballantine Books, Bob Pepper, dark fantasy, fantasy, Horror, Joe Mugnaini, Ray Bradbury, short fiction, weird fiction, Weird Tales

“…that thing on the shelf, why couldn’t it be sort of— all things? Lots of things. All kinds of life— death— I don’t know. Mix rain and sun and muck and jelly, all that together. Grass and snakes and children and mist and all the nights and days in the dead canebrake. Why’s it have to be one thing? Maybe it’s lots.”

Ray Bradbury’s early years are easy to overlook, as even many of his devoted fans do these days. Bradbury sharpened his pen in the pulp ghetto, writing for magazines like Planet Stories, Thrilling Wonder Stories, and (worst of all) Weird Tales, mags that SF trufans often looked down upon as unscientific fluff or pure juvenile schlock, unworthy competition for Astounding. Within a decade, the pulps were dead, and Bradbury was all but a household name, skipping Astounding entirely to sell his wares to more mainstream (and up-market) magazines like Collier’s and Playboy. That led to some resentment in certain SF writers and editors, having failed on their own to break into the better-paying market, now seeing a young turk best known for space opera and ghost stories make the jump. The joke’s on them, because Bradbury became one of the best-known and most influential writers of his time.

The October Country is the largest and most notable collection of Bradbury’s pulp years. Most of the stories were first published in Weird Tales; 15 were pulled from the earlier Arkham collection Dark Carnival, with four original to the volume. Coming from Weird Tales, and with a title like The October Country, I think you can see where this is going: these stories have a distinct edge of horror, comprised of seedy carnivals and dark-lit alleys and dead old things, peopled by the bizarre outcasts of a sane society.

Fear, here, is the primary focus. “Skeleton” deals with a man who thinks his skeleton is out to get him, crawling around beneath his skin with strange alien malevolence, but the alternate solution of visiting a “bone specialist” leads to an ending that’s just as horrific. “The Small Assassin” is about a woman terrified that her baby is trying to kill her. Let that sink in for a moment, both as an example of how terrifying and uncomfortable some of these stories can be. “The Wind” has a man terrified about the wind, a steady and innocuous breeze that may hide its own killer secrets. “The Crowd” deals with a man terrified of the strangers who gather at auto accidents, the crowd who decides who lives and who dies.

“The Next in Line,” one of the best stories in the collection, has a young couple touring Mexico stop by the local cemetery to view the mummies—unearthed remains of the deceased, whose relatives are too poor to pay ongoing rent for a long-term grave space. The wife is haunted by visions of the mummies, paranoid she will end up like one of them, locked in the crypt’s slow dry decay. Her husband’s lack of concern becomes maddening when their car breaks down and they are stuck with no way to leave town; she attempts to keep her panic in check, but her fears escalate with each minute they spend in town. It’s a gripping tale of psychological suspense, and one of the best of Bradbury’s early tales.

Another winner is “The Jar,” filmed as an episode for one of Alfred Hitchcock’s series. A hillbilly visits a carnival and is fascinated by the bizarre growth housed in a freakshow jar. He becomes so fascinated by it that he spends a whopping sum, twelve dollars, to buy it outright. It fills void in his life as other folks from town will stop by his house; they religiously stay well into the evening to sit and ponder what it could be—rather, what it means to them: a missing child, a repressed memory, a manifestation of evil or sin. Charlie enjoys his newfound popularity as much as he enjoys his jar, but his cheating wife hopes to shame him by telling Charlie and his peers what’s really in the jar. That’s her final mistake, the realization of just what this jar means to Charlie. The next day, the jar’s contents are remarkably more defined…

Even when they have a positive ending, these are not heartwarming stories with happy outcomes—they’re still overflowing in macabre morbidity, drowning in a strange, murky atmosphere. “Uncle Einar” is a glum man because of his surreal green wings, which have caused him to live segregated from “normal” society with his pretty young wife. I can see it as one of Bradbury’s recurring metaphors for creativity, or living outside of fear, as Uncle Einar just needs the inspiration to fly and acknowledge his unique gift. “The Lake” is about a boy who saw a girl swim out to the center of his hometown lake and drown; when he returns a man, with a wife/girlfriend in tow, she makes a morbid reappearance. “The Cistern” is a similar tale, a morbid love story about a girl who dreams about two dead bodies in love, swaying forever in the churning waters of the nearby rain cistern. “There Was An Old Woman” may be one of the happiest, and it’s about an old woman who decides she will defy death, even after the reaper goes and steals her body right out from under her.

“The Emissary” is another great example. Martin is a boy who’s suffered from an unknown illness, bed-bound and trapped in isolation. His emissary to the outside world is his dog, Dog; Martin puts a note on Dog’s collar inviting strangers to visit. His schoolteacher does, and he enjoys several days of fun before she dies suddenly in a car crash. And as Halloween approaches, even Dog goes missing. But never fear—Dog does return, damp and dirty and reeking of fresh grave loam. And he’s completed his mission, bringing someone back to visit with Martin… It manages to hit both of Bradbury’s main styles, being both a heart-warming tale of childhood nostalgia, and a morbid story of the dread fantastic.

Bradbury’s talent is not fully defined at this early point of his career; there are flashes of his poetic brilliance and voracious vocabulary, thrashing beneath the surface, enough so that the stories are unmistakably his. If Something Wicked This Way Comes is Bradbury’s poetic imagery unrestrained, this is his prose starting to emerge and dominate. What sets the collection apart is how Bradbury’s wild imagination combines with his prose; it’s like a chemical reaction guaranteed to keep you glued to the page in abject fascination. Bradbury would make several other visits to tales of gothic terror, with Something Wicked and The Halloween Tree, becoming such a small but vibrant part of his oeuvre in the face of hundreds of other stories. Yet his horror fiction is no less compelling, no less inspired, as the best of his SF or fantasies. As a classic in the genre, it’s a must-read, perhaps even a must-read-every-year, a good volume to break out and peruse in the days where noons go quickly, dusks and twilights linger, and midnights stay. Don’t be scared away from a “horror” collection, as it’s really quite accessible; take a long and evenful trip to The October Country.

Book Details

Title: The October Country

Author: Ray Bradbury

Publisher: Harper Perennial Modern Classics

Release Date: 2011

What I Read: ebook

Price I Paid: $1.99 (Kindle sale)

ISBN/ASIN: 034532448X / B00C4TJACE

First Published: 1955 (short stories, 1943-54)

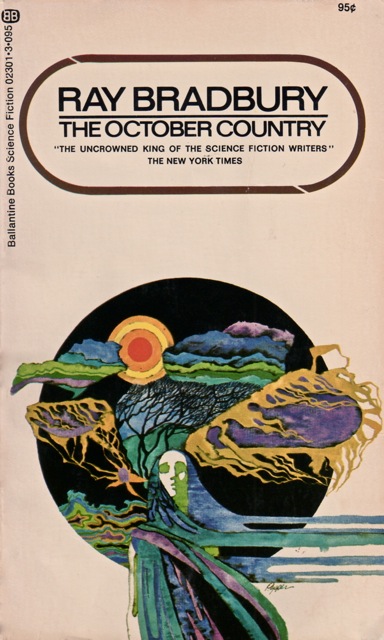

That 1955 Joe Mugnaini cover is very nice. Haven’t seen that cover before.

LikeLiked by 2 people

It’s a sharp cover. Mugnaini also did the interior illustrations, all in the same style as that cover.

LikeLike

Great review Chris (and I love the covers) – Bradbury, via THE ILLUSTRATED MAN and THE MARTIAN CHRONICLES, was the first serious author I ever read as a kid, closely followed by Raymond Chandler and then William Faulkner – I still think that’s pretty much the right order to read these great American writers 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Sergio. I agree, pretty much the right order! I also read lots and lots of Bradbury as a kid, then Chandler and Hammett, but didn’t read Faulkner until later in school. That’s when I found out what I had been missing 🙂

LikeLike

Great review! I would snag this today but I’m already behind on the ol tbr 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks! You had a pretty heavy load after your last draw, and that’s not including your mysterious shadow list… there’s always next year? Also: now you’ve got me looking for a copy of Destiny Times Three, haha!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good! You’ll love DT3! I’m finishing Grass today, btw. It’s kind of perfect for Halloween, which I didn’t expect. This planet is terrifying.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, Grass had a surprising amount of horror in it — that would be the LAST planet I would ever want to visit, where the people are classist jerks and the animals all want to kill you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sorry I never read this one,although I knew of it.I think from what I know of his work,he was at his peak in the 1950s.In the next decade,novels such as “Something Wicked This Way Comes” and “The Hallowen Tree”,are not as good I think as “The Martian Chronicles” and “Dandelion Wine”,which can’t really stand beside the radicalism of the young authors then emerging.

I think what you say about his early stuff being the start of his best work,is pertinent in this case.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I mostly agree… I consider him at his peak in the ’50s—so many iconic stories came out of the decade, or the very early ’60s—but I also consider Something Wicked to be his high-water mark. No, it doesn’t stand alongside the radical young authors then emerging, but I think that’s comparing apples to oranges… Most of those authors were interested in experimenting with style and expanding (or inverting) genre, while Bradbury is more just a pure storyteller. Something Wicked is Bradbury at his stylistic peak, like he opened the tap to pure 200-proof Bradbury and just let the poetic imagery and lush vocabulary flow into a chilling, dark, and metaphor-laden story.

LikeLike

During the 1950s,Bradbury was unusual for writing in a quaint,literary style long before the start of the psychadelic age.It wasn’t surprising he was becoming recognised as a great author,as well as one in the sf genre.That talent didn’t diminish of course,but unlike the earlier,seminal 1950s novels I mentioned,”Something Wicked This Way Comes” offered nothing that could be called expermental I think.

No,he couldn’t be compared to the next generation of authors,and “Something Wicked This Way Comes” probably wouldn’t have been a bad novel if it hadn’t have been published at a time such as J.G.Ballard’s “The Drowned World” and Philip K.Dick’s “The Man in the High Castle”.In comparison to those,he was waring himself thin I think.

LikeLike

This has always been my favorite of Bradbury’s collections. I felt he reached a peak around this time, a peak that was followed by a long decline into flabby self-indulgence.

I read the book in, I’m pretty certain, the UK Penguin edition, and until now haven’t really been aware of those tremendous covers you’ve chosen. Many thanks for them, and for your absorbing review.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, John! I have to agree, his earlier works were full of stories that were sharp and iconic, but as the decades progressed those become harder to find. When you said “self-indulgent” his mystery novels immediately came to mind…

LikeLike

Joe Mugnaini worked closely with Bradbury. I like this cover for October Country the best. The first edition cover for Fahrenheit 451 is very good too.

LikeLiked by 2 people

That cover, and his interior illustrations, are great. And his cover for Fahrenheit 451 is amazing, a real classic… There’s a reason publishers keep reusing parts of it for reprints, but I don’t think they’re as good as the original.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also – you make a good argument regarding Bradbury’s literary standing – how his jump up to the ‘majors’ without really spending much time at the traditional Sci-fi magazines would be a source of some jealousy.

LikeLike

A terrific review of an essential horror collection. I read OCTOBER COUNTRY for the first time a few years back and wished I had read it as a kid!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Does Bradbury’s work need to be referred to as horror? Like science fiction,it’s roots lie in Gothic fiction.His stuff including his science fiction,can definetly be described as Gothic,as can other authors writing within the science fiction genre.His work partakes of quite a few genres.

That he caught the attention of mainstream literature,shows he wasn’t recognised as particularly belonging to any division.

LikeLike

Bradbury is an fantasist who defies and transcends genre, his stories often slipping between them. But as Will states, this collection is unmistakably one of horror. There is nothing SFnal about it, very little of whimsy or nostalgic glee here. It collects the sound of rustling leaves, the scent of damp wormy earth, and the feeling of the hairs on the back of your neck standing on edge.

LikeLike

Myself, I’ve never thought of The October Country as a horror collection. I think the stories in it fall neatly into the category that’s today called “weird fiction.”

As I say, this is probably my favorite of his collections, unless you count (as you quite reasonably could) Dandelion Wine as a collection; that‘s the book of his that really blows me away.

Of course, you could also think of The Martian Chronicles as a collection, although for me it’s certainly a mosaic novel.

And, yes, you’re right in a comment you made elsewhere: the mystery novels were certainly jostling at the forefront of my mind when I mentioned the flabby self-indulgence. There was also a late collection of his that I had to read for review that was just a mess of slop, lots of wonderful images (and some dreadful ones) thrown together without much of an attempt to make sure things made sense, or were even coherent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It definitely fits the description of Weird Fiction; if published today it would probably get that label, as would works by Matheson, Beaumont, etc. Though, weird fiction often skirts the lines between horror, fantasy, and suspense.

Martian Chronicles is a great book but to me it reads clearly like a fixup or mosaic novel. It’s framed as one collected work, but doesn’t quite align seamlessly.

Dandelion Wine! speaking of excellent books I really should reread. I recently bought copies of it and its late sequel, Farewell, Summer, but now I’m worried the latter is the mess of slop collection you referred to…

LikeLike

It was From the Dust Returned (2001). I had to go to Wikipedia to check this, because I’d forgotten (blanked out) the title, and I see that it’s classified as a fixup novel. Hmmf. Yeah, right.

Also at Wikipedia, there’s interesting stuff about the genesis of both The Martian Chronicles and Dandelion Wine. This makes me very much more inclined to try the two later-published “Summer” fixups, which I’d assumed were later-written and thus likely to be less interesting.

LikeLike

Science fiction I find impossible to define.Certainly as you say,it’s not science fiction though,but the way you describe it,is what I mean by Gothic.Also,as you say,he transcends genre,and I don’t like to label anything he writes,including stuff by him that can be called science fiction.

As I say,I can’t come up with a real definition of science fiction.The best I can say is,that it’s a catergory there for the convinience of publishers so they know where to market their books.I much prefer to call it all speculative fiction,that’s fluid enough to contain elements of all genres.I don’t think anything less can be said for the excellent Ray Bradbury.

LikeLike

Thanks! I’m actually in the same boat… The Martian Chronicles was one of the first “adult” books I read, and I’ve read a couple of these stories before in other Bradbury collections, but this was the first time I read all of October Country. Now that i know what I was missing, I wish I’d read it years ago!

LikeLike

Hi

I loved your comments about Bradbury’s place in SF. Certainly as a teen I read a ton of his stories which were very much SF in my mind. I had been haunted by 3 stories I vaguely recalled reading as a teen but could not remember the title/author and I finally realized all were by Bradbury, Frost and Fire, The Man and Pillar of Fire. Bradbury as one might expect from an author associated with Weird Tales and Arkham house has a strong horror element, but there should be enough aliens, rocket ships other planets for any SF buff. Other writers associated with Planet Stories like Moore and Hamilton are clearly considered SF writers but people seemed ambivalent about Bradbury. City by Simak is considered a classic but is also is very much a fixup novel based on short stories. So I am not sure why Clarke, Heinlein and Asimov are the big three and Ray get little love. Thanks for your review of October Country I really enjoyed your take on this book and Bradbury as a writer.

Regards

Guy

LikeLike

H.P.Lovecraft also wrote for “Weird Tales”.His stuff contained strong elements of science fiction tropes within a strong Gothic framework,but like Bradbury,he clearly transcended genre confines.

LikeLike

Thanks, Guy! Ray was always one of my favorites… Funny that you mention Simak’s City since that’s another favorite. Like you I’m not sure why Clarke, Asimov and Heinlein are the big three of SF — well, I guess I know, I just don’t prefer their works — but I think Bradbury’s importance in the genre is secure.

LikeLike

They had a greater popularity than Bradbury,that’s why I think.It’s probably because they aren’t as great as him,that they are.Literary brilliance isn’t always going to be important for to achieve that.

LikeLike

Great piece Admiral, some lovely covers too – I particularly like the Ballantine. All the best.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent review. I have a copy sitting on my shelf that I clearly need to bump higher on the TBR List. My copy is reproduction of that first Mugnaini cover.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Matt! I remember your fantastic review of Fahrenheit 451; while this collection is rougher, it’s also quite diverse and quite good. I have the feeling you’ll really like parts of it… it’s weird fiction from before that was a thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Before it was a genre you mean.Everybody imitated Bradbury.It was truly an original.

LikeLike

Pingback: 2015 In Review | Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased

Pingback: F&SF – March, 1956 | Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased