Tags

1940s, 1943, dark fantasy, fantasy, Fritz Leiber, Horror, pulp, Tor Doubles, Unknown Worlds, urban fantasy, Wayne Barlowe, witchcraft

Ace wasn’t the only company to do a lengthy line of tête-bêche/dos-a-dos double novels. Tor Books, founded in 1980 by former Ace editor Tom Doherty, did a short but vibrant line of Tor Doubles starting in 1988. The line was dominated by authors who were hot topics in the late ’80s/early ’90s: Greg Bear, Timothy Zahn, Kim Stanley Robinson, Gene Wolfe. But there were a large number of reprinted classics, showing some quality taste in the editors’ choices. The best was probably Leigh Brackett’s Nemesis from Terra backed by her husband Ed Hamilton’s Battle For the Stars, but there was also Brackett’s Sword of Rhiannon, Vance’s Dragon Masters, Silverberg’s Hawksbill Station… and the last Tor Double, number 36 from 1991, contained Fritz Leiber’s classic Conjure Wife backed with his Our Lady of Darkness.

Fritz Leiber is best remembered for his Lankhmar tales, featuring swordsmen Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser. I can argue with myself back and forth over who is the best sword-and-sorcery author, but I find Fafhrd and the Mouser to be more vibrant and interesting characters than Conan or Kull or Kane. Licensing Lankhmar to TSR for use with Dungeons & Dragons paid Leiber’s bills during the later years of his life, though he had a long writing career. He was an early participant in the Lovecraft circle before turning out his own science fiction yarns, the best-remembered probably being “Coming Attraction.” Well before his Lankhmar compilations took off in the late ’60s, Leiber’s first penned novel was the dark fantasy Conjure Wife, for a 1943 issue of Unknown Worlds.

It is the people we know best who can, on rare occasions, seem most unreal to us. For a moment the familiar face registers as merely an arbitrary arrangement of colored surfaces, without even the shadowy personality with which we invest a strange face glimpsed on the street.

Norman Saylor is a rational college professor at the rural college of Hempnell. As an ethnographer he’s made his academic career studying superstitions—but he doesn’t believe in it. Until he goes searching through his wife Tansy’s dressing room on a whim, and discovers little charms and supplies for practicing witchcraft. Tansy arrives home at that moment, and Norman, over the course of the evening, convinces her that it’s a neurosis with no basis in science and that she should drop the crazy habit. She does. But as the last charm is thrown into their fireplace, Norman has a bad feeling…

Then strange things start happening around Norman. There’s the angry phone calls in the middle of the night, mentally unstable students start bothering Norman. There’s his colleagues, competing with him for department chair, uncovering coincidences between his thesis and an earlier one by another scholar, and dealing with his crazed students. Plus his colleagues’ wives, a batch of odious women if there ever was one. Last of all, and most important, there’s that stone dragon on the roof of the lecture hall next to Norman’s office, which he could swear is moving closer every day… but that would be illogical and silly, as would telling Tansy, so Norman stays quiet as the coincidences accumulate.

I found the novel hard to get into (though not as bad as Our Lady); the first chapter consists of Norman’s interior monologue pontificating on sociology and ethnology, Hempnell politics, his colleagues, their conservative attitude, his wild and reckless lifestyle. A lot of dry world building, not a lot of hook outside a great first paragraph. Give it time; the novel begins to build steam: the next chapters build a tangible feeling of dread unease, as many coincidences point to forthcoming danger. The atmosphere is great, which sets the stage for the finale, and when the ante is upped, the plot starts moving fast. True, there are a few more over-analytical Norman chapters later, when he’s trying to rationalize how this new science of sorcery works. But after the few chapters, the novel starts building some incredible tension and atmosphere.

It’s an odd blend of dark fantasy and urban fantasy. (Well, urban fantasy in that it’s modern; Hempnell is set off in some placid rural area.) The dark fantasy parts are pretty obvious—witchcraft, sorcery, the supernatural—but the feelings of lurking horror and dread give it the solid horror backbone which enables dark fantasy to work.

Leiber’s prose alternates between good and competent; there are a few visual flashes which indicate his creative genius, and he handles the creation of atmosphere and tension like a master, but the novel has some painful writing flaws. First would be the overuse of “-ly” adverbs, the first thing you’re told to get rid of in any writing workshop. Maybe I’m just too keen on spotting them, but this novel was rife with these crappy adverbs, enough that they bothered me. Leiber also has Norman sit around musing over what he’s seen too often, which felt like a forced attempt to remind us we’re dealing with a logical, rational, card-holding member of the collegiate intelligentsia. It’s not bad enough to ruin the horror mood, but it does take you out of the suspenseful action.

As you’d might guess from a novel written in 1943, Conjure Wife is dated. There’s a strong “behind every man is a good woman,” happy hausfrau mentality here, which comes off as sexist, but isn’t helped by Norman’s realization that a woman’s irrationality and traditionalist mentality is what allows her to channel magic. All women are witches, while most men are prevented from gaining this power due to their cold, rational logic. You could argue that it does empower women—they’re the movers-and-shakers in occult power—but I’m not going to make that argument. Nor am I going to defend the book’s references to “Negroes” and “southern Negro superstition.” No overtly hostile racism or misogyny, but it is very much a product of its time.

Of course, the time period also makes the characters’ wild lifestyle look even more out of place with their Hempnell colleagues: drunken shenanigans and evading the night watchman during the ’70s or today is one thing, doing so during Prohibition sounds dirtier. Hempnell is portrayed as a very traditional, conservative, “hometown America” kind of place, while Norman and Tansy reminisce about their wild and carefree past. Norman’s also pretty antagonistic in his discussions and lectures, running contradictory to the Hempnell party line, like Leiber’s trying to paint him as a radical pedagogue, a stereotype Norman’s monologue debunked in the first chapter.

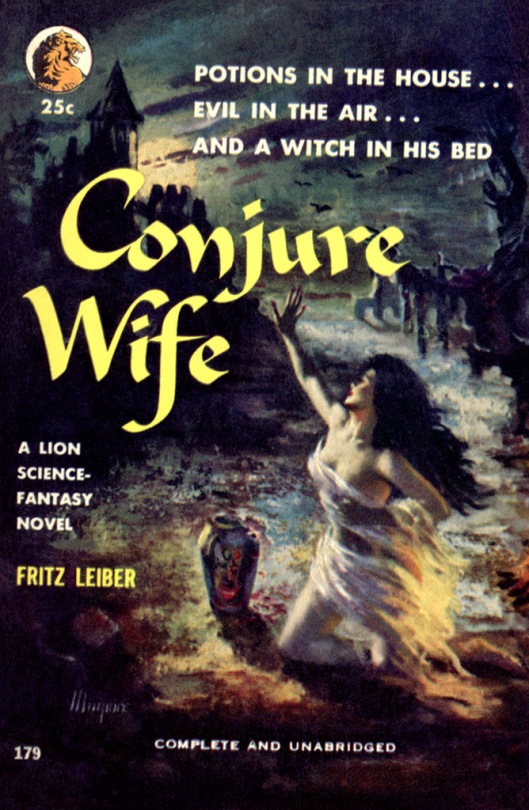

Lion Books 179 - 1953. Very moody and atmospheric cover, great gothic overtones... but it has nothing to do with the novel.

Conjure Wife was first serialized in the pulp Unknown Worlds in 1943, and appeared in paperback from Lion Books ten years later. (It saw serial publication again in Marvel’s short-lived Haunt of Horror digest.) It’s been in consistent print since, hitting all the major paperback sellers: Award Books, Berkley, Ace, Penguin, and Tor, who published it in the aforementioned double in 1991 with Our Lady of Darkness. Tor’s classic reprint imprint, Orb, has printed the book twice in the near past: the double in trade paperback form as Dark Ladies (1999), and Conjure Wife on its own a few years ago (2009), with a rather underwhelming cover. (Hoping to popularize off the new dark fantasy boom following Twilight I guess.) Note that the double’s cover isn’t from Conjure Wife but Our Lady; speaking of having little to do with the story.

The story was also filmed three times thus far, around every two decades: Weird Woman in 1944 (with Jon Chaney Jr.), Burn, Witch, Burn!/Night of the Eagle in 1962, and Witches’ Brew in 1980. There’s supposed to be another version in the works due out in 2012, keeping with the every-few-decades release dates. It’s also hard to imagine that it didn’t influence Bewitched at all, though its portrayal of house-witches (witch-wives?) is lighter and comic. (Obviously.)

On the back cover, noted critic and short-story writer Damon Knight proclaims:

Easily the most frightening (and necessarily) the most thoroughly convincing of all modern horror stories… Leiber has never written anything better.

That may have been accurate in 1967 when Knight penned it, but Leiber’s later material is much, much better. Conjure Wife was early in Leiber’s career—again, his first novel—and the man learned a lot in the decades to come. Conjure Wife has enough adverbs to grate on my editorial nerves, and the pacing is jolted by those occasional “I don’t think I’ve reminded you in the past ten chapters that Norman’s a professor of sociology who likes to rationalize stuff” segments. Technical complaints and comparisons aside, the plot, pacing, and tension this novel builds is amazing. Age has tarnished the novel, but it is far from rusted over. The way it holds up is remarkable: while it dates itself, Conjure Wife is still as engaging and chilling today as in the 1940s.

Pingback: Horror Movie Review – Burn, Witch, Burn! (Night of the Eagle) « Logic is my Virgin Sacrifice to Reality

Lot of research here. Good review. Tnks

LikeLike