Fredric Brown was one of those unique, elusive authors who was equally successful in both the mystery and science-fiction genres. About half my readers probably know Fredric Brown from novels like The Fabulous Clipjoint and The Screaming Mimi, his many and well-regarded mystery/noirs. The other half probably knows him for What Mad Universe or Martians, Go Home, comical science-fiction novels parodying the genre’s tropes and fandom. (I should amend that to say Brown is known for these novels “if at all” because he’s less well known than he should be.) The Lights in the Sky are Stars is one of his often overlooked 1950s novels; instead of a comic SF satire, it’s a serious affair about “man’s ceaseless drive to new frontiers” from the mid-1950s.

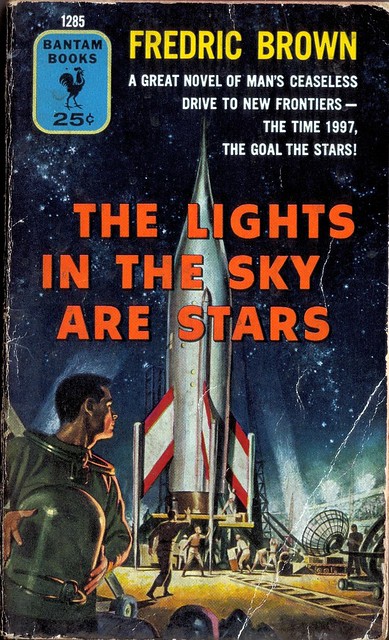

Bantam #1285 – 1955 – illo by Mitchell Hooks. I think Hooks was a very underrated artist, though this cover makes me think of a Heinlein-style juvenile.

It is the future; the year is 1997. Humanity reached Mars in 1964, five years ahead of its schedule for the first lunar landing, but space exploration came to a halt after reaching Venus. Max Andrews was one of the brave rocket pilots who opened up the stars, but losing a leg on Venus forced him out of space exploration and into the role of drifter and rocket mechanic. All that changes when he catches wind of Ellen Gallagher; word has leaked that should she win her bid to become a Californian senator, she’ll push through a bill for a rocket flight to explore Jupiter. It strikes a chord with Max’s dream of star-flight, and he does everything in his power to complete the Jupiter rocket project—nearing sixty, he knows he won’t be able to pilot it himself. But as he grows closer to Ellen, he find himself slated for the director’s seat. This novel describes five years’ worth of struggle and political maneuvering, from cheerful enthusiasm to crushing loss, as he puts Jupiter within reach.

First and foremost, this is a very optimistic book—they just don’t make them like they used to. The world in the novel is a mirror of our own, where the majority of people don’t see any value in space exploration or visiting other stars, seeing it as dangerous and economically wasteful; Max’s first-person narration is an exuberant, almost desperate optimism to find out what’s at some alien star, placing him in the vocal minority. Behind his unscrupulous tactics—he’s willing to break the law to get this project rolling—and his noir-lite dialogue, Max is like a child staring wide-eyed into the starry night. Max is enthralled by the potential of the great unknown, embodying the sense of wonder about wonder itself. That gives the novel a certain charm; it offers many parallels to the loss of interest in space exploration in the real world.

The Lights in the Sky presents a vision of space travel that’s a bit closer to home than most SF books that came before it; it’s not the impromptu creation of some genius free-agent/mad scientist, it’s a complex governmental project. Max and Ellen have to cut through a lot of red tape, navigating the murky labyrinth of politics to make sure the project gets the votes it needs to succeed—there’s a lot of hard work to be done long before actual construction begins. Really, there’s a lot more political wrangling and back-door dealing than you’d expect: despite the cover blurbs, this isn’t a space adventure, it’s the book about building the rocket that undertakes the space adventures. As Max is a less-than-scrupulous fellow, he fits right in to the gray world of nepotism and self-interest; the novel’s vision of space exploration may be rooted in ’50s optimism, but its cynical vision of politics is timeless.

The Lights in the Sky presents a vision of space travel that’s a bit closer to home than most SF books that came before it; it’s not the impromptu creation of some genius free-agent/mad scientist, it’s a complex governmental project. Max and Ellen have to cut through a lot of red tape, navigating the murky labyrinth of politics to make sure the project gets the votes it needs to succeed—there’s a lot of hard work to be done long before actual construction begins. Really, there’s a lot more political wrangling and back-door dealing than you’d expect: despite the cover blurbs, this isn’t a space adventure, it’s the book about building the rocket that undertakes the space adventures. As Max is a less-than-scrupulous fellow, he fits right in to the gray world of nepotism and self-interest; the novel’s vision of space exploration may be rooted in ’50s optimism, but its cynical vision of politics is timeless.

Brown’s prose has some moments of brilliance, but novel has too many info-dumps of pure exposition; Max likes to tell a lot about space exploration history, and about not just his past but that of all his friends, and it gets tedious after a while. (Even Ellen shoots down some of his history lessons, when he’s telling her things she already knows.) There’s not a lot of action: we learn the history leading up to a key moment, and then a “six weeks later” recap of how that key moment happened and what’s happened since. So, there’s an abundance of exposition info-dumps; on top of that, Max is something of a fanatic—you know from very early on that his grand plan isn’t just to see this rocket built, it’s to hijack it for himself so he can catch one more ride into space. You know it, he knows it, every one of his friends knows it. His fanaticism for space travel works as both an asset and a hindrance for the novel, because his one-track mind is pretty one-dimensional at times.

All of Max’s enthusiasm and cheerfulness telegraph the novel’s plot for the most part, and even the surprise setbacks aren’t much of a surprise. Yet after a series of semi-predictable developments, there’s a couple of emotional blows that the novel delivers—one I expected, the other came out of the blue—and together, they moved the book in a whole ‘nother direction. There’s also the sympathetic presentation of M’Bassi, the last of the Masai warriors, seeking his own metaphysical, spiritual pathway to the stars. There’s some deep and interesting content hidden behind all those times where the protagonist lectured future-history at us, and looking at those smaller elements gives the book a more forceful meaning—another take on hope and will, the things that power Max’s optimistic fervor.

I found Lights in the Sky to be a mixed bag: the story is unique, and the hopeful optimism is something that’s always resonated with me about SF. Dry exposition is ladled on with gusto, and Max’s optimistic fervor begins to wear thin halfway through the novel, but the novel’s enthusiastic charm makes it something of a fun ’50s romp. It’s a story about one man’s sense of wonder, instead of the typical story meant to inspire a sense of wonder in the reader. And the last twist and metaphysical subplot, its serious tone compared to Brown’s other SF works, make it a unique point of interest. The Lights in the Sky are Stars is a flawed novel, but I found its strengths outweigh the frequent expository info-dumps. Then again, the potential wonder of space travel captured me at an early age, so I’m biased in favor of the novel’s uplifting vision.

Despite purchasing it three years ago, I put off reading Lights in the Sky are Stars since the reviews I saw were so mixed—some people consider it (and Rogue In Space) Brown’s worst SF; others consider it an awe-inspiring novel, an uplifting gem. For those who do read it, I hope it falls into the latter category.

A great coverage of a great novel. Myself, I think that Brown was one of the great masters of the short (and especially short-short) story form, and that his novels are by comparison a bit slight. But The Lights in the Sky are Stars (along with, perhaps, The Screaming Mimi) is the exception that, y’know, wotzit.

By the way, it’s “Fredric”, not “Frederic”; just thought I oughta be the PITA editor.

LikeLike

I have to agree, just about every short story I’ve read by Brown has been excellent. I haven’t read many of his novels, but I picked up a few more last month to see how they fare. And I’m sitting here with a half-dozen of them right under my eyes and I didn’t notice I was misspelling his name, argh. Thanks for the kind words and the editorial catch.

LikeLike

Great review chum (glad to say I own a copy of the 1963 Bantam edition) and I think very fair.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My guess at the 1963 cover artist would be Dean Ellis.

LikeLike

Great article on a great book. You said the Hooks cover was a bit juvenile but I have to say it gives me goosebumps. All the best.

LikeLike

I dig the Hooks cover (great angle), probably should have explained it better but I’d meant it looked like a Heinlein-style juvenile.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Book Review: Fredric Brown’s The Lights in the Sky Are Stars (variant title: Project Jupiter) (1953), M. A. Foster’s Waves (1980), Eric Frank Russell’s The Great Explosion (1962) | Science Fiction and Other Suspect Ruminations

Pingback: Short Book Reviews: Fredric Brown’s The Lights in the Sky Are Stars (variant title: Project Jupiter) (1953), M. A. Foster’s Waves (1980), Eric Frank Russell’s The Great Explosion (1962) | Science Fiction and Other Suspect Ruminations