Tags

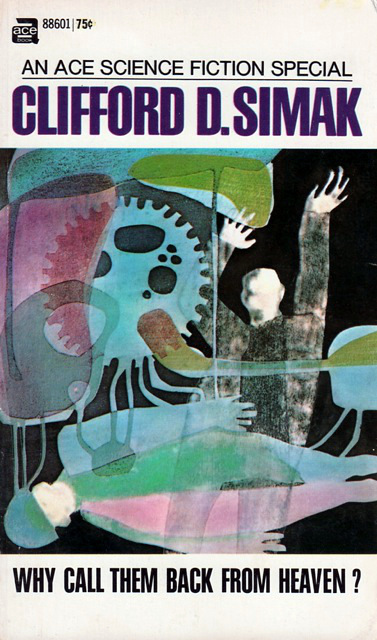

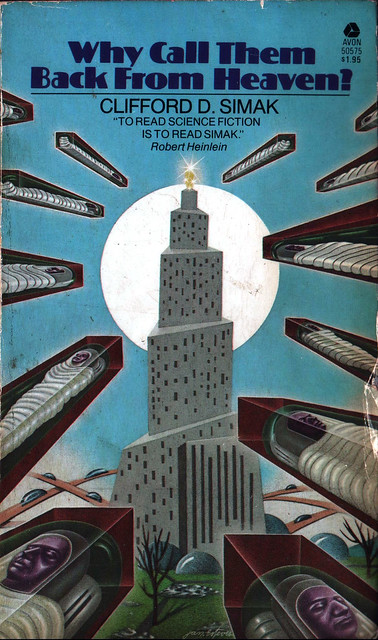

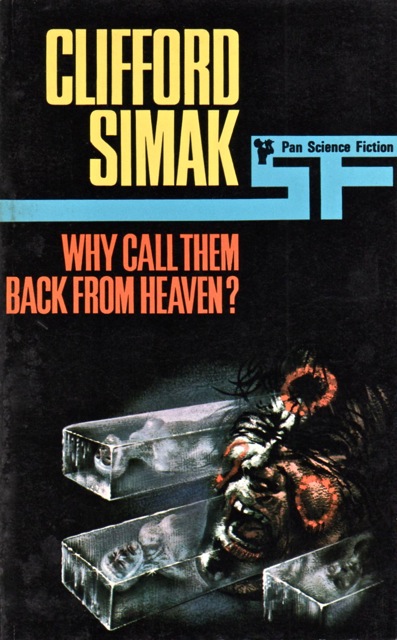

1960s, 1967, Ace Books, Ace Science Fiction Specials, Avon Books, Clifford Simak, dystopian, immortality, Leo and Diane Dillon, New Wave SF, overpopulation, religion

Clifford Simak never achieved the familiarity and name recognition that Asimov and Heinlein did, though most in-the-know SF fans have seen some of his works on best-of lists and compendiums. A newspaper man, Simak’s first hardback novel was the fixup Cosmic Engineers (1950), though he’d been writing the future since 1931—Cosmic Engineers itself was first serialized in Astounding in 1939. I’ve enjoyed Simak’s style of pastoral science fiction, particularly City (one of the best SF works originating in the 1940s) and the Hugo-winning Way Station. My assumption is that Simak is now lumped as a Golden Age author, but the bulk of his novels were written after 1960, when he started writing one a year. While his later works made his repetition in style and theme clear—the pastoral, elegiac elements SFE referred to as “Wisconsin-valley fantasy”—and saw his mournful tone replaced by whimsy, they also showed some evolution as a writer, matching those elements to more creative ideas and some really entertaining novels: Time is the Simplest Thing, A Choice of Gods, and perhaps the best-named of all his books, Why Call Them Back From Heaven?

By 2148, most of the world is controlled by Forever Center, a private company that cryogenically preserves the dead and is working to find immortality. Most people scrimp and save during their lives for the perfection promised by Forever Center—immortality, rebirth from cold storage into a young body. Death or imprisonment are no longer punishments with immortality to look forward to, and war has ceased to exist; even ostracization from the human race has the promise of rebirth into a young body, even if you can bring nothing of value into your future—the worst punishment one can suffer is being cut off from that promise of immortality, your life forced to end at the time of death. Paying citizens are allowed to bring items into their new lives, and so stockpile coins, stamps, artworks, tracts of land, all in expectation that these trinkets will accrue capital and gain interest as their owner lies dead through the centuries. Meanwhile, Forever Center puts their funds to good use, preserving their land, buying stock in other companies, to the point where the company has more power than most governments.

Daniel Frost is one of Forever Center’s executives, whose job is to ferret-out and censor those who are critical of immortality or Forever Center—particularly from religious groups, who find this artificial replacement for divine immortality intolerable. Daniel has a few political adversaries at work, and he may have been sent some important—potentially indicting—files by accident; not wanting to condemn himself, he passes them off sight unseen to attorney Ann Harrison, who showed up on Frost’s doorstep hoping he could help reverse the verdict that cut her client off from immortality. It turns out Daniel hasn’t acted fast enough, and he finds himself ostracized from humanity—hunted by an unknown faction, having stumbled onto a secret that some would kill for.

The novel uses a non-traditional structure that alternates between Daniel’s story and a series of short vignettes, displaying a number of characters and settings across the city. Some are single snapshots, such as two men playing chess in the park while discussing Forever Center rumors, or the salesman talking a couple into purchasing a tract of swampland as a future investment. Other characters are returned to once or twice: Ann’s previous client, Franklin Chapman, starts the novel and is a recurring point-of-view character. Chapman’s a lost soul condemned to live and die a mortal life for his sins: a driver of rescue cars that drive out and preserve those who’ve died, his vehicle broke down and prevented a paying customer from reaching the cryonic embrace. Another few chapters follow a Catholic priest whom Chapman visited for guidance, who undergoes a crisis of faith when he realizes what Chapman is denied, when the priest himself has doubled-down on the afterlife by signing up with Forever Center. It adds up to some amazing world-building, showing so many elements—it’s a superbly defined setting.

Unlike several of Simak’s earlier novels, the theme here isn’t the pastoral return to nature, but an overpopulated earth where Future Center is scrambling to find living space—either a habitable planet, or the secret of time-travel that would unlock the untamed lands of aeons past. The third act changes that, when Daniel undertakes his flight from both city and corporation in search of his old family farm, alluding to a return back to more pastoral, traditional roots. The characterization is hit-or-miss—Daniel is somewhat generic, and most characters remain bit players in Daniel’s story, though Ann is an interesting and quite capable female lead and Chapman is very well-drawn. Simak’s writing was never flashy, always capable but unadorned, and here it loses some of the emotional weight that his previous works captured—City, for instance, is something of a dirge for humanity. What carries the novel are its deep metaphorical/philosophical themes, and the strength of its setting. I’m surprised Simak didn’t snag an award for this book, since it’s one of his best attempts at penning the literary SF novel.

If you couldn’t tell from the title and setup, Simak makes heavy use of religion as a metaphor—the conflict between Forever Center’s physical immortality and the Judeo-Christian heaven, such as the underground guerrilla movements that rebel against Forever Center’s promised afterlife in favor of one provided by traditional belief. (The rebels are neither overtly sympathetic or overbearing in their zeal, striking the fine balance as believable characters caught up in an oppressive world.) The big picture gives even more food for thought. Capitalism and religion have become blended in the hopes and dreams of Forever Center, echoing several religions I could name. The masses live in poverty, scraping and saving for their salvation—not by buying indulgences or purification, but living a miserable life now to pay Forever Center to live like a king after their rebirth. When they come back, they hope, they will cash out their petty goods—stamps, coins, art, jade—bringing their treasures into the hereafter like the pharaohs of old. The difference between the Forever Center of the 2100s and the Catholic Church of the 1500s is that one is selling a promise based on religious faith, the other on scientific faith—both are made of equal parts belief and expectation. It’s metaphors layering metaphors.

Why Call Them Back is not a book loaded down with action or dramatic tension, and it lacks the emotional weight behind many of Simak’s most successful novels. But Simak is a deft writer who takes the reader on a fascinating exploration of some philosophical themes: the ramifications of Forever Center’s promise; the premise of immortality as mankind’s salvation. And the world-building is superb thanks to the vignettes inter-woven into the main plot, giving a wide-angle view of the setting. These elements put Why Call Them Back From Heaven? on another level—it’s the kind of book that will richly reward the reflective reader. Simak has penned a subdued but contemplative novel that has aged rather well. It won’t appeal to readers who equate science fiction with space opera, but it remains an overlooked New Wave classic. Does it make the best introduction to Simak? That’s debatable. But I think it has more deeper meaning than many of his other works. Recommended to all science fiction readers, especially those looking for themes of immortality, overpopulation, or religion.

This is by far my favorite of Simak’s novels — and I’ve read quite a few. I think you nail the reasons: meaning-drenched, carefully planned out structurally and conceptually, literary (in some ways), and occupying a fantastic and realized world. Has my highest endorsement!

(P.S. great review)

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂 I remembered your review from last year, which is why I tracked it down—so, thanks for that one! Agreed, this one was both the best-written and the most inventive of all his novels I’ve read so far.

LikeLike

Great review! This is the last of Simak’s novels that I really liked; after this, I too often found them flat, uninspired or just plain silly. But his output up to this point was exemplary: a superb body of work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, John. I agree, an excellent body of work, even if his fiction went downhill in the 1970s and ’80s… I think A Choice of Gods is the main one from that period that I’m interested in reading. But there are several of his 1960s novels to read first!

LikeLike

I found his 70s work rather flat as well — did not care for A Choice of Gods (as you know from my review). The entire pastoral wonderfulness falls flat when you have nice robots to help you do all the work and are magically ageless and free of disease…

LikeLike

“…subdued but contemplative novel that has aged rather well.”

This sounds right up my alley, and it’s on my list already! You make it sound better than Way Station and I loved Way Station!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have raved about this one as well. And you like my suggestions 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Just saw your review. I must have missed it. It was posted back when I was new and thought you liked weird-sounding books that I would never enjoy 😛

LikeLiked by 1 person

You thought I liked books you’d never enjoy? Boo. I don’t think my tastes are THAT strange (other than Malzberg etc).

LikeLike

It was back when I didn’t know a think about it. I didn’t think I’d like vintage SF that much.

Obviously things have changed since then. 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha, i know. I’m jesting. But really, read this Simak. I can’t imagine you wouldn’t enjoy it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s on the TBR and I’m looking forward to it. I may have to move it up!

LikeLike

Don’t remember which was your first vintage read, bit I do remember those Couch reviews of Heinlein and ’30s pulp… Loved the “what the hell did I just read” vibes. When that’s your “vintage” sf I can’t blame you for not thinking you’d like it 😛

Could be worse, I started this blog so I could complain about all the bad 70s novels I’d read: Riverworld, Fred Pohl’s Jem… SOMEONE may have convinced me it wasn’t such a bad decade after all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve read the early classics (Verne, Bradbury, Wells) off and on all my life, but I think my first real vintage read was Stranger in a Strange Land. And I’ve loved Heinlein ever since… I also love to stab myself in the eyeball.

I’m still having “what the hell did I just read” moments. I don’t think that will ever stop.

And I’m glad SOMEONE convinced you to be nice to the ’70s.

LikeLike

I used to review a lot more of the 70s crap…. There is a ton of it. But, I find it more and more difficult to actually soldier a bad novel these days. For whatever reason.

The very first SF novel I read was a “vintage” read — Asimov’s The Currents of Space. I read it again a few years back and it was pretty awful. I don’t think I started reading SF compulsively (I enjoyed fantasy) until I went through the Hugo Award list. And then I ran out of the “Famous” novels (at that time I meant simply those that had won awards) and explored my favorite author’s back catalogues (Brunner etc).

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t think my tastes are THAT strange (other than Malzberg etc).

Malzberg isn’t a “strange taste”!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think he is… Most people cannot tolerate his visions. I am a compulsive fan of his work 🙂

LikeLike

You’ve convinced me that I finally need to pick up my $0.25 ex-library copy and start reading. The last Simak I read, Ring Around the Sun, was quite decent and left me intending to come back to him.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The last Simak I read, Ring Around the Sun, was quite decent

I’ve always had a soft spot for that one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Always nice to see Simak getting some attention.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think I have only ever sampled his short stories in anthologies and none of his novels. I enjoyed the review but from what you say I don’t think this is where I would necessarily want to start – if not here, where would you recommend?

LikeLike

Way Station is a pretty safe bet, one of his most popular titles. It’s a bit dry since it’s his earliest work but City is a personal favorite.

LikeLike

Thanks Chris – will pursue!

LikeLike

Great review Admiral and the first two covers are very special. I have this with the Dillon cover. All the best.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: (dis)connectivism: a learning theory for the ghost in the machine « Dave Parsons' NZ IT Academia blog