Tags

1940s, 1945, Dell, Dorothy B. Hughes, hardboiled, noir, Pocket Books, psychological, suspense, trains!

Famine and War. War breeding destruction. The Horsemen of Chaos waiting their time. Madness. Hell. Once he hadn’t believed in hell. Once he hadn’t believed in a personal demoniac deity. But he’d seen men possessed. He knew powers of evil flogged the earth and powers of good weren’t strong enough to exorcise them. The powers of good, what had happened to them? Where was heaven? If there was hell, there must be heaven. There must be the balance.

He said bitterly, “We have to die to get to heaven.”

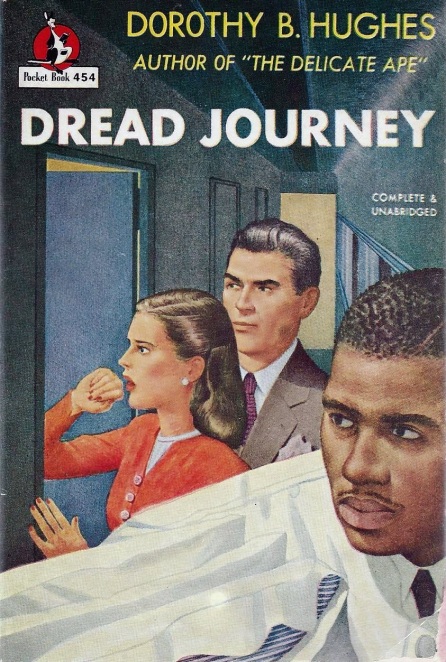

Dorothy Hughes was one of the grand old dames of noir, one of the more popular writers of mysteries and thrillers in the 1940s. Her writing career began to slow in the early 1950s, and while she won an Edgar in 1951 and published a few books in later decades—1963’s The Expendable Man received some critical acclaim—her most prolific period was during the war years. While she’s often cited as one of the best women authors to pen hardboiled noir, many of her books have been out of print and forgotten until the recent past—a real surprise, since they were so positively received when first published. It was Anthony Boucher’s rave review of Hughes’ work, in particular a review of Dread Journey, that convinced me to give Dorothy Hughes a look—“This is Mrs. Hughes’ finest book to date and not to be missed under any circumstances. You heard me.”

She was afraid. It wasn’t a tremble of fear. It was a dark hood hanging over her head. She was meant to die. That was why she was on the Chief speeding eastward. This was her bier.

Aboard the Chief, a passenger train chugging along from Los Angeles to New York, Kitten Agnew knows she is going to die. She’s under contract to star as Clavdia in an adaptation of Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, a film that director Viv Spender has been meaning to make for ages. Kitten is the last in a long line of starlets groomed for the role, only to be cast aside at the last minute as Vivian Spender becomes obsessed with another, younger starlet he imagines will make a superior Clavdia and complete his masterpiece. If only these young women didn’t meet unfortunate ends—suicide by overdose of sleeping pills in the case of the last one, Viv’s wife. But even as Kitten is forced to share a suite with Gratia, the naïve young Newfoundland beauty that Viv has picked as the next Clavdia, she is unwilling to give up without a fight. Kitten has an iron-clad contract on the role, and her lawyer—uncle to a previous failed, dead Clavdia—is eager to take Viv Spender to court. Thus, Kitten knows she will either land the role of her dreams or die in some nefarious accident aboard the Chief.

Also on the train are a cast of washed-up Hollywood dregs. Leslie Augustin is an award-winning band leader and composer, but also something of a lecherous playboy looking for drink and dames; he may have struck gold after locking eyes with the innocent Gratia. Hank Cavanaugh is his drinking buddy, once a hotshot reporter now completing his descent to the bottom of a whisky bottle: broken by reporting on immense poverty and famine in China, and cracked for good after spending too much time on the Pacific Front. Sidney Pringle once had dreams of becoming the Great American Novelist now bumming a ride back home to the safety of his mother, a failed screenwriter who’s just as broken and shamed as Hank—crushed by his own pride and failures, devastated by his own ego. Also aboard are some couples more than thrilled to see such Hollywood icons in their same car, living their vacations or honeymoons without knowing Kitten’s immense dread.

The confined space of the Chief makes an excellent setting for a thriller: there is nowhere for Kitten to run or hide from Viv’s manipulations. The characters are thrust together in enclosed spaces, boozing it up for one reason or another, forced to share the same limited space. Their histories and failures overflow and spill out onto their neighbors, as the enclosed spaces means the gossip has a shorter distance to travel. That also means that Kitten’s plight is known to the others—all of them sense the tense fear in her body and dread in her eyes… All but Sidney and Gratia, one stuck in his own little world and the other blissfully unaware of the cynical motives of others.

That confined space also means that the head porter, James Cobbett, sees and knows all. Because of his low station in life due to class and race, Cobbett is overlooked and underestimated by all the other characters—a fascinating use of race in a 1940s novel! That he’s a black man isn’t even identified until halfway through the novel, and I’d assumed he had been whitewashed until Hughes mentioned it in passing. Cobbett may identify the characters with their room numbers due to the hundreds of people he serves in a month, but his profession and servitude to the others hides a keen, quiet intelligence. As a decent family man, Cobbett is also one of the most “normal” out of all the characters: most of them follow the cliche of self-absorbed Hollywood bigshots, wrapped up in their own desires and dramas. Despite that, all the characters are vivid and three-dimensional—it’s just that Cobbett is more well-drawn, an everyman to draw the reader into the story and let them see everything.

Dorothy Hughes’ writing is an intense concoction of suspense, and I’d argue it’s some of the best hardboiled prose from the 1940s. Where earlier writers in the hardboiled school took Hemingway-style modernism to its extremes, Hughes somehow manages to improve on those hardboiled stalwarts in the same way. Every single word she uses is chosen with the utmost care and precision; every single sentence carries a heavy weight, creating an atmosphere of grim unease even with the simplest sentences describing mundane events. It’s a noir thriller of the finest craftsmanship. Hughes crafts an evocative and predatory world waiting to spring on characters made vulnerable by their damaged pasts—though some will find the innate tenacity to hold their ground.

Dread Journey falls about as close to perfection as a book can get. The setting is an ideal confined space for suspense, and Hughes’ execution of the plot makes no mis-steps, using well-drawn characters and setting to the fullest. The excellent prose makes it a joy to read, compelling the reader onward by the weight of the oppressive tension. The suspense begins on page one, and doesn’t relent until the electrifying ending. Boucher was right—not to be missed, under any circumstances. That’s an order. Dorothy Hughes had her heyday in the 1940s, but in the last few years she’s begun to receive some long-overdue recognition. Books like this one show that the acclaim is more than deserved. Dread Journey is a must-read for anyone who considers themselves well-versed in suspense or noir but has yet to read a Hughes novel—you need to see what you’ve been missing out on.

Well, I’m completely sold – I’ll get myself a copy and then feedback chum – thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Enjoy Sergio — curious to see what you think!

LikeLike

Splendid review! I must find a copy of this. I loved the only novel of hers I’ve read, In a Lonely Place, and keep meaning to read more.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks John! Good to hear you enjoyed In A Lonely Place, as the film version seemed quite good… it is one of the two other Hughes novels I own.

LikeLike

The movie is one of my all-time favorites, if you’ll forgive the link, but it and the book are really two quite separate entities: the same elements are deployed in the service of two different stories. Which is actually great news, because essentially you’re getting two great pieces for the price of one!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: 2015 In Review | Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased