Tags

1970s, 1973, Ace Books, Ace Double, crime, Doris Piserchia, investigation, Kelly Freas, New Wave SF, science fiction, time travel, vigilante

Science Fiction’s “New Wave”—the more experimental period in the late-’60s, early-’70s—is full of now-forgotten authors, such as Doris Piserchia. Piserchia’s career took a while to blossom: while her first short-story, “Rocket to Gehenna,” was first printed in 1966, her writing career didn’t really get started until 1973. That was when she wrote her first novel, Mister Justice; after that, her career took off. In the space of ten years she wrote thirteen novels, most of them science fiction paperback originals for DAW Books. Her works saw her associated with the US New Wave; two of her later novels were horror, under the pseudonym “Curt Selby.” And her exit from the genre was as spontaneous as her entrance: her last book was released in 1983, and that was all–she never wrote another SF piece again.

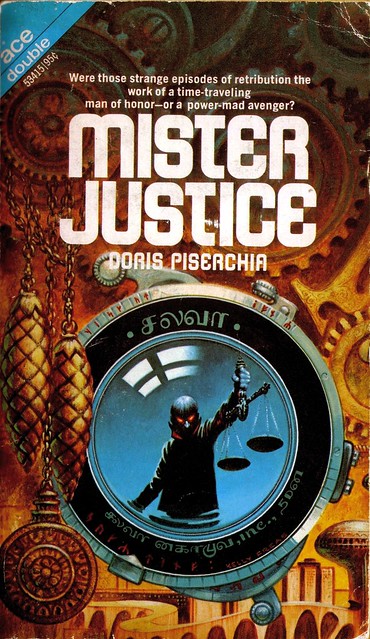

Ace Double 53415 – 1973 – illo by Frank Kelly Freas. I know not everyone is a fan of Freas, but I find his covers enjoyable enough. (Note: for Freas, time travel book = clocks on cover.)

In an America where the justice system seems to be breaking down, a time-travelling vigilante going by the name Mister Justice is striking at criminals: after photographing their crimes in the past, he arrives in the future to enact revenge. Most criminals meet the same fate as their victims, but after a plea from the President, they are found in front of police stations bound and gagged and loaded down with incriminating evidence. The authorities cannot allow this spate of vigilantism to continue, and a triumvirate of Secret Service agents take young supergenius Daniel Jordan and train him to catch Mister Justice—conscripting a superboy to take on a superman. Meanwhile, one criminal seems to escape Mister Justice’s best efforts, a kingpin named Arthur Bingle, another time-traveller who’s begun to take over the world.

That sounds like a very neat plot structure, but the novel has a number of entwined subplots. Daniel’s training begins at a special school for eccentric geniuses, where he falls into a romance with Pala, an eleven-year-old Swiss orphan. (Shades of van Vogt’s supermen mixed with Heinlein’s inappropriate romances.) Pala is kidnapped during Daniel’s investigation, which throws him into despair. Later in the book, the focus is on Bingle and his cronies as they consolidate power; the government and police have collapsed into little more than licensed brigands, and Bingle’s army of “Numbers” make their move. It’s not clear whether society was already collapsing when Mister Justice began punishing criminals, or if he was part of the tipping point that caused a loss of faith in the justice system; that said, it wasn’t in that great a shape to begin with, when Mister Justice exposes the vice president as a criminal that the justice department has no interest in prosecuting.

The prose style is… unique? Parts of it are very dry and pulpy, simple “He did this. He thought that.” sentences. They become a chore when ten of them are stacked together to form a paragraph. (This is very true for the first chapter and early parts of chapter two; if you bear with it, the writing does improve.) Other times, the prose has a murky, dreamlike quality to it, snippets of greater brilliance that build later in the novel. The characters speak in oblique dialogue, and while it’s easy to piece together their meaning at times, I always felt like there was more going on than the story was willing to tell me. The structure, on the other hand, is always a hot mess. Piserchia has odd preferences for structure and appears to despise paragraph breaks; at one point, between one connected sentence and another is an unannounced time jump of some six years. Some of this can be construed as New Wave experimentation, and with some patience and attention to detail most things are obvious even if they were not spelled out. But it makes the novel a challenging read when the book itself actively works against the reader.

I saw several people refer to Mister Justice as Piserchia’s best novel, which leaves me very apprehensive: I have five more of her books, and if this one is the best I can’t imagine how the others are. Her imagination is beyond brilliant, and the plot is full of excellent elements—the premise is great, many of its plot-threads are full of potential, and with a little work it could have been a New Wave classic of crime and punishment, or a surreal homage to the pulps. It’s a remarkable book. But Mister Justice felt like a novel condensed into a novella, leaving valuable context on the cutting room floor. It’s almost too spontaneous and subtle for a casual read, and won’t go over well with readers expecting traditional structure and coherence, but it could satiate fans looking for a stylistic New Wave SF deep cut that most will overlook. There’s enough positive reviews on the Doris Piserchia website to tell me it does have its fans.

I saw several people refer to Mister Justice as Piserchia’s best novel, which leaves me very apprehensive: I have five more of her books, and if this one is the best I can’t imagine how the others are. Her imagination is beyond brilliant, and the plot is full of excellent elements—the premise is great, many of its plot-threads are full of potential, and with a little work it could have been a New Wave classic of crime and punishment, or a surreal homage to the pulps. It’s a remarkable book. But Mister Justice felt like a novel condensed into a novella, leaving valuable context on the cutting room floor. It’s almost too spontaneous and subtle for a casual read, and won’t go over well with readers expecting traditional structure and coherence, but it could satiate fans looking for a stylistic New Wave SF deep cut that most will overlook. There’s enough positive reviews on the Doris Piserchia website to tell me it does have its fans.

I wrote about this one back in 2004 and reprinted my comments last week. (http://billcrider.blogspot.com/2015/03/ffb-mr-justice-doris-pischeria.html) I had some of the same feelings you did about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hah, nice timing! I remember reading your comments when I first bought and researched this double, several years ago, and your assessment is spot-on.

LikeLike

Sounds right up my street this does, I must start doing some digging to see if I can find that Freas cover…and it’s an Ace Double to boot! Thanks for the tip Admiral, all the best.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And there’s a pretty good Freas cover on the back, too, for the novel Hierarchies by John T. Phillifent. Enjoy 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I remember reading a remainder hardback of this fairly quickly a long time ago and not thinking much of it. This was probably in the mid-80s and I had already read all of her other books, including the two Shelby titles. Actually I still have 9 of her books on the shelves in the study… Anyway, I was a bit of a fan but really didn’t take to Mr. Justice at all.

My favourite is Doomtime, followed by her two ‘monster’ novels, The Spinner and The Fluger. If you have 5 more of her books, chances are that you’ll have at least one of them!

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s good to hear. The Spinner is indeed one of the volumes I own… I will read it next out of her novels, but I assume at least one of them I’ll find more appealing than this one.

LikeLike

I reviewed A Billion Days of Earth by Piserchia and enjoyed it. Although, more due to the bizarre imagery, strange plot, unusual aliens, odd events than the prose. Which could be beautiful but was more often rather stilted.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that definitely describes Mister Justice, very stilted—and kinda pulpy, like it was a pastiche of a ’30s hero pulp—but remarkable and bizarre ideas/plot. Not much imagery though, and no aliens. Don’t have that one but will pick it up if I find it, your review made me curious. (It’s also the first result Google gives me, fyi.)

LikeLike

Another author I am completely unschooled in (hitherton 🙂 ) – thanks Chris. Must admit, sounds like a book that is possibly more interesting to talk about than to read!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m really not sure why I’ve bothered keeping so many of her books! Apart from Mister Justice and the two Shelby books (not bad, but poor sellers, iirc) the only title I haven’t kept is Star Rider, her 2nd novel.

Something about her 3rd, A Billion Days of Earth, appealed to me and after that I read the DAW books as they came out.

I think I kept so many not because i was sure they were good, but because I couldn’t decide whether they were or not!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha, good to know… Since you and Joachim both found something appealing in A Billion Days of Earth I guess I should have tried that one.

LikeLike

That was teenage me that read it; apart from liking it enough to read more of her, I remember very little about it. I had read Star Rider previously, so although I’ve not kept it, it must have been interesting enough for me to try another…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Note #11 in this list of 12 sf books that broke the mould!

http://scottishbooktrust.com/reading/book-lists/12-science-fiction-books-that-broke-the-mould

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha… Quite a lot of good books on there. That pretty much convinces me I have to read Billion Days, if only to see what all the fuss is about!

LikeLike

To be honest, I think sf continued on pretty much unaffected by her work, but I may be wrong. Your fresh eye may see a trend I’ve not connected to her work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Mister Justice, Doris Piserchia | SF Mistressworks

Pingback: Mister Justice – Doris Piserchia | The Scotto Grotto (org)