Tags

1970s, 1972, alternate history, Avon Books, Cold War, Nazis!, Nebula Award nominee, New Wave SF, Norman Spinrad, post apocalyptic, Prix Tour-Apollo Award winner, science fiction, social satire, World War II

Science fiction—case in point, alternate history—is a genre that seems specifically built to play “what-if” scenarios about Adolf Hitler. What if Hitler had won the war (The Man in the High Castle)? What if he was assassinated before he became Führer (Elleander Morning)? What if they Nazis had been invaded by aliens (Marching Through Georgia)? What if he hadn’t done this or that—not invading Russia but finishing off England first, or waiting several more years before starting the war to develop more weapons? What if the Nazis had developed the first atomic bomb?

Or, here’s one. What if Hitler had been a failed politician, leaving Germany for America in 1919 to become another European immigrant, then followed up on his dream to become an artist? What if he’d sold illustrations to fellow European migrant Hugo Gernsback’s magazine Amazing Stories, and been enthralled by the possibilities of science fiction? If Adolf Hitler lived in this alternate world and was not a man who’d lead millions into death and misery, what kind of science fiction would he write—would his dreams of conquest, his belief in eugenics and genetic purity, would those become “harmless” works of pulp fiction instead of reality? Norman Spinrad took that idea and ran with it, building an extensive alternate history and, in an act of metafictional brilliance, wrote one of Hitler’s pulp novels. For those who loved such classics as The Thousand Year Rule, The Master Race, or Triumph of the Will, here’s the 1954 Hugo-winning classic whose vivid future and iconic uniforms still inspire cosplayers of today: Lord of the Swastikas.

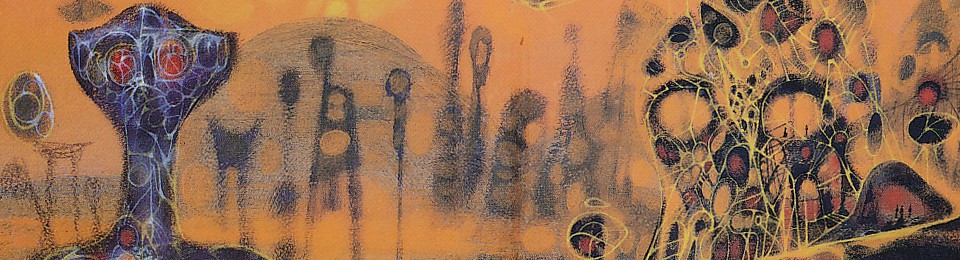

Avon #N448 – 1972 – artist unknown, but they did a great job capturing the crazed elements of the novel: Feric wields the Great Truncheon of Held above the heads of ignoble mutants.

Lord of the Swastikas forms the novel-within-a-novel, and aside from the scholarly introduction and afterward, is pretty much the extent of The Iron Dream. Feric Jaggar, Trueman, journeys to his ancestral Heldor (Not Germany), last bastion of genetically pure humans in the aftermath of nuclear apocalypse. Most of the surrounding nations are full of “pure mutants and mongrelized crosses and human-mutant hybrids” and others of genetic impurity. But Feric is disgusted to find Heldor in a state of disarray, allowing mutants into its borders to do manual labor. He even finds a Dominator (Not Jews), a mutant with psychic powers who corrupt and control the minds of others and an affront to Truemen. Feric sets forth to right these wrongs, first joining and gaining control of the Human Renaissance Party (Not NSDAP), then becoming the leader to a motorcycle gang that forms the basis of his Knights of the Swastika (Not Sturmabteilung). As he gains power and influence, he leads his Swastika Squad troops (Not Schutzstaffel) to invade the Dominator-controlled Zind (Not Russia).

Thus, Feric Jaggar is a stand-in for the real-world Adolf Hitler, and the apocalyptic future of impure mutants sets the stage to mirror Hitler’s rise to power. Spinrad takes some liberties in the plotting—the Beer Hall Putsch and Night of the Long Knives occur at the same time, after the Heldor equivalent of a “March on Rome” (which Hitler much admired) and just before the invasion of Russia—and as this is a fictional Hitler’s fantasy, it stops being a mirror of reality and provides an alternate ending for our genetic Trueman heroes to get the victory they so desire.

Spinrad’s inclusion of an afterword by fictional New York University professor Homer Whipple, a scholarly analysis “spelled out by a tendentious pedant in words of one syllable.” Indeed, Whipple seems more interested in pointing out the homoerotic undertones and pointing out every phallic symbol in the story, though it’s through him that we see the world in which Lord of the Swastikas was written—the Iron Curtain has fallen across the globe, with only North America and the Imperial Japanese Empire standing strong against international Communism. What gives this entire novel punch is this afterword, especially when it ponders if this work could have really happened. In the grimmest of black humor Whipple calls Jaggar’s rise to power and crusade against the eastern untermensch ludicrous, declaring “it can’t happen here.” If only it were an alternate history… though as Whipple’s alternate world points out, “different” does not necessarily mean “better.” That’s the satire right there, a pretty damning indictment of both humanity and pulp adventure SF.

The writing is a spot-on jibe at all types of SF, a send-up to: simplistic pulp adventure stories from the olden age; the sword-and-sorcery narrative of a brutal male undertaking an epic quest and rising from nothing with the aid of a magical weapon; the faux-Tolkien fantasy industry featuring heroes cutting a swath through “sub-human” species (ethically acceptable because they’re called Orcs and not Jews); the Hard SF fetishism of machines and devices (the countours and grace of which are lovingly described by Feric). It’s a kind of rebuttal to Heinlein’s oligarchic tendancies, and Hubbard’s pulps’ lurid prose and outdated views on gender and culture. It’s a slam against old stories like Armageddon 2419, the first “Buck Rogers” tale, as much a work about the “yellow peril” as it is a work of adventure SF. It also suggests the use of ancient races and ethnic stereotypes in Lovecraftian fiction. The use of “genetic” reminded me of Dickson’s The Genetic General—variant title of Dorsai!, speaking of militaristic alpha-male fantasies. John Norman’s atrocious Gor series is about the type of SF this is satirizing; perhaps it’s best Hitler/Spinrad doesn’t include any female characters, avoiding any rape or torture thereof.

Still, despite the brilliance of its idea The Iron Dream is imperfect. Le Guin touches on the novel’s high points and failings in her analysis, and for the most part I found her opinion spot-on. Hitler was not a very good artist, and doesn’t make for a very good pulp author either; while I appreciate what Spinrad was doing, the Nazi wish-fulfillment/wet-dream male fantasy joke starts to drag after a few chapters, and I wish it’d been a punchy novella instead of a dense novel—it feels twice as long as it needs to be. (To be fair, it did seem to pick up later on, but that could be because I was skimming.) The reader gets the joke early on, but still the novel continues; the high points crest as memorable bits of satire, but between them are troughs of tedious polemic. The bad writing is part of the point, as is the retelling of alt-Hitler’s fictional rise to power through his Gary Stu stand-in Feric Jaggar, but just because Spinrad was being smart by writing tedious prose doesn’t make that prose any better or more readable. It becomes cloying after a while; reading “genetic” as often as Asimov would use “atomic” as verb, noun, and prefix—or as often as any of Lovecraft’s unspeakable, cyclopean, non-Euclidean repetitions—can make it disturbing and uncomfortable.

The Iron Dream takes an absurd idea and turns it into great satire. Lord of the Swastikas is a dreadful read, dreadful by intent but dreadful nonetheless. Perhaps it isn’t as bad for readers who can disconnect themselves from the repugnant ideology it faux-promotes, and read it with less arms-length detachment than I could. And some readers do miss the point, per Spinrad, finding it a rousing adventure story soiled by “all this muck about Hitler.” As an experimental and very metafictional novel, I think its success depends on the reader’s tolerance and taste: Lord of the Swastikas lacks believable, sympathetic characters, avoids tension and drama, and is a mess of repetition and bad plotting. That’s the joke, but I don’t think it carries for 255 pages. If you enjoy the metafictional satire of alpha-male fantasies, you’ll be able to slog through it; otherwise, you’re probably better off skimming through to the afterword, rather than slog through one long and tedious joke just to arrive at an 11-page punchline. While I applaud the idea, I found the execution tiring.

I read this book when it appeared in 1972 and was impressed. Maybe it was the times. I’ve often thought about read it again, but so far I’ve resisted the urge. Judging by your review, that seems like a gold thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It could very well just be me, since I’ve seen several glowing reviews for it. Definitely a great idea behind it, and some rather sharp satire as well.

LikeLike

Great review. I too skimmed near the end of the novel proper (to get to the afterword). Although I found the concept, delivery, etc all very satisfying.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know you rank it near the top of your list, and the central idea + afterword are downright brilliant. Found the prose a bit too over-the-top purplish though, and the non-stop tirades on genetic (im)purity probably got to me more than they should have.

LikeLike

I love the idea in the commentary the author claims that this sort of thing can never happen. Which is the power of the work — we might write SF which advocates this racist ideas and not see the incredible harm and damage they cause and might cause.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very true. It’s why I’ve held off on reading military SF stuff, Dorsai! for example, and your average epic fantasy. It works if you take the good-and-evil, black-and-white at face value. Any degree of moral relativism and the whole thing breaks down.

LikeLike

Yikes, it does sound like a great idea, but a bit much in execution. Great review.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed—an excellent idea on paper, but not one that will resonate with every reader. Thanks!

LikeLike

That is one batshit crazy concept for a novel. I need to read this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

No argument there 🙂 Look forward to your take on it!

LikeLike

Thanks for the review.

I agree that the novel is too long. The pointed criticism of the fascistic tendencies in pulp sf is good but mostly implicit – a wink to those in the know. Now wonder real fascists like this novel. The satire breaks down with the grim and relentless retelling of the Nazi war and even worse, the fantasy victory of fascist panspermia. A truly horrific vision that left me depressed despite its ludicrous regiser. I think Spinrad was a bit naïve to think that he could inoculate his work from undesirable attention.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very much agree—without knowing the genre references, a lot of the book’s satiric value is lost. And I found it depressing as well, and started reading a comedy about halfway through The Iron Dream to take the edge off.

LikeLike

I still recommend this book to people with assorted caveats, particularly its place with regard to the new wave and the criticism of the pulps. Its the type of book you wish would work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent review! I read this not long after it came out in UK paperback and recall having the same reservations you mention. But a wonderfully ambitious premise: take nothing away from the author for that.

Er: afterword.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks John, and thanks for the catch; I swear I know the difference 😉

LikeLike

Great review! This is one I will have to read one day, simply because it was on Joachim’s Masterworks wishlist. (The goal is to read everybody’s choices eventually.) I haven’t read Spinrad before, but I know he’s on my TBR for something else… can’t remember at the moment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s a great goal—I read it for more or less the same reason, Joachim has praised it several times, and after it made his Masterworks list I picked up a copy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This sounds wonderful – can’t wait to get hold of a copy. Great review chum.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m interested in reading this. Though the alternate-history angle – and the obvious references to actual historic elements – seem unavoidable, I have a strange ability to remove those things from the front end of the storytelling and put my thoughts into the world as presented by the author. Perhaps this defeats the intent of the work, but for me it allows a sort of unpolluted look at the given world making it a more genuine personal experience and the freedom to determine its value on my own terms. (If that makes any sense)

Thanks for bringing the novel to my attention – as well as the thought provoking review!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Scout, I’m sort of confused by your comment. The entire point of the novel is that it does mirror what actually did happen. This is Hitler’s wet dream, this is his desire which is never manifested in this timeline. The pseudo-scholarly conclusion claims that “such things can never happen” but obviously, because of our knowledge of Hitler and what he did–and because you as the reader recognizes the same pattern of events from his life unfolding in a SF setting–the satirical point that pulp SF can be dangerous in its racism, etc hits home like hammer…

LikeLike

Yeah, I kind of alluded to your point in my original comment, Joachim. But, imagine that somehow in the future the memory of Hitler and the Third Reich is erased from history, and, The Iron Dream was strangely preserved somewhere. Would the ideas and events in that novel hold any value (for good or for bad) on its own account?

That approach may defeat the original intent of the author, but it forces the work to stand on its own merits (or not). It’s an odd approach, I suppose.

LikeLike

I do not believe that texts exist in vacuums. Their contexts (cultural/textual), their author’s intentions, are ALL vital in understanding and appreciating and assessing merit in a work.

Likewise, we cannot appraise a work without our own contexts and cultural knowledge and shared (sometimes) memories.

So, I don’t know how that viewpoint is possible or useful.

LikeLike

I do not believe that texts exist in vacuums. Their contexts (cultural/textual), their author’s intentions, are ALL vital in understanding and appreciating and assessing merit in a work.

Likewise, we cannot appraise a work without our own contexts and cultural knowledge and shared (sometimes) memories.

So, I don’t know how that viewpoint is possible or useful.

But no, the work is worthless if you don’t know something about history or anything about Hitler’s legacy. The book would not have been made nor would it be possible to read now.

LikeLike

Joachim, I never suggested that one should remove their own context and cultural knowledge – just the reverse. I’m encouraging that as a matter of fact.

Are you saying that without knowing an author’s intent you can’t formulate your own ideas about a literary piece of work? I find that sadly lacking in imagination. But, as I contemplate the larger meaning of it I realize that perhaps it’s not very rare. Heavens forbid that people start to think on their own.

How do you deal with an original piece of fiction? Do you need to read reviews and listen to all the author’s interviews before it starts to make any sense?

Wow.

LikeLike

Ok, this has gone somewhat far. My apologies.

(Of course not, to your last point. But yes, I do like to know something about the author. But intent can often be figured out by reading closely and knowing something about the rest of SF at the time. Why else would I focus so much on a period? To get a nice grasp of the era)

LikeLike

I think Joachim’s coming on a bit strong, but I agree with him that context creates value when reading, and this in particular is a hard book to remove yourself from—its strongest elements are allegory and satire, which I’d argue require context. An author’s intent doesn’t dictate what readers see in their work. But in a world that didn’t remember Hitler, and especially for a world without pulp SF, The Iron Dream wouldn’t make much sense. From a craft perspective, it’s not very well put together, which was the point. From a worldbuilding/sensawunda view, I’d have to assume it’d be vaguely repugnant unless you share a particular philosophy. Maybe from just story, but that gains added value by comparing it to Hitler’s rise to power. So I’d be very interested to see what you think about the book, since I’m finding it hard to see your approach.

LikeLike

Thanks much for your reasonable diplomacy, admiral. This whole conversation takes me back to my University days when I took English lit – fortunately, the grades were based on written mid-term and final exams rather than participation in class discussions. I found myself trying to explain my method for my ideas more than the ideas themselves, eventually I learned how to keep silent. In the end, my professors appreciated reading an exam that wasn’t parroting those ideas tossed about in common discourse.

With all that said, I rarely add comments on blogs but your review stirred my thoughts enough that I thought I’d share my interest and perspective. If/when I read the novel I will send you my thoughts via email – I think you’ll get what I’m saying once you read my interpretation. Then again, if the book is as poorly written as you seem to suggest, it may not lend itself to anything worth saying. We’ll see.

Thanks again.

LikeLike