Tags

1950s, 1954, Adventure, apocalyptic, Appendix N, Ballantine Adult Fantasy, bleak, Boris Vallejo, fantasy, George Barr, Gollancz Fantasy Masterworks, myth, Norse mythology, Open Road Media, Poul Anderson, vikings!

Poul Anderson is best known for his hard science fiction, but he also wrote a number of fantasy novels—described as “fantasy with rivets” in his New York Times obituary. Three Hearts and Three Lions is one of the more famous, The Broken Sword being the other; I’ve already reviewed the former, so I’m moving on to the latter. The Broken Sword was released in 1954, just months from when the first small printing of The Lord of the Rings was shipped to the U.S.. That makes it—quite literally—one of the last pre-Tolkien works, and yet also one of the first works of mainstream fantasy, transitioning from fairy-tales and sword-and-sorcery pulp to become its own genre.

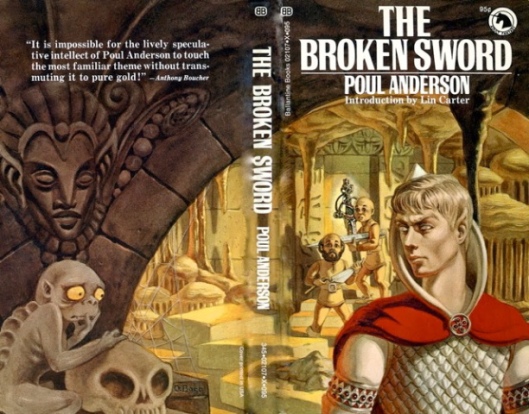

Ballantine Adult Fantasy – 1971 – George Barr. The BAF was perhaps the greatest collection of fantasy in the 20th century.

Anderson writes a tale based on the folklore of the changeling, told from both sides. Orm is a viking in England, off pillaging when his son is born; before he can be baptized or brought into the way of the Norse gods, the child is stolen away by Imric the elf-lord to the realm of faerie—another world that exists just beyond the world of mortals—and is renamed Skafloc. Left behind is the changeling Valgard, who Orm raises as his own son. Skafloc learns the magic and swordplay of the elves, while Valgard becomes a viking berserker. But the fates of these two young men—one a dark mirror to the other—is entwined. Skafloc is drawn into the elves’ war with the trolls, Valgard goes insane, slays his foster-family, and joins with the trolls. As the war intensifies, and the trolls begin an assault on Elfheim, their paths will cross again and again, foreshadowing an epic showdown that will seal the war’s fate.

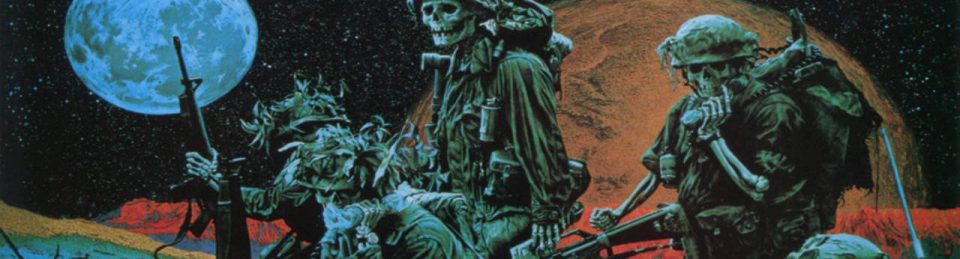

And mischance falls upon ill luck with increasing frequency. The Broken Sword is a pretty grim book, awash in misery and death; there are no happy endings, and as one ill portent leads to another, you realize how Skafloc and his allies are fated for miserable ends. Valgard may be the “bad” mirror image of Skafloc, but when pushed to the brink, Skafloc acts like his changeling replacement. Even happy developments only bring later suffering. After Skafloc saves a pretty young maiden named Freda from Valgard and the trolls, the two young humans quickly fall in love, Freda bringing out Skafloc’s dormant humanity after years of only knowing the elves’ love-less society. But what we know as readers, and what the characters don’t know, is that Freda is Orm’s daughter, and thus Skafloc’s sister by blood—and, as I recall my mythology, this kind of love only ever ends in tears. If Shakespeare had written this novel, we’d call it a tragedy. For a tragedy it is, writ large in the grim spectacle of Wagnerian apocalypse.

Anderson’s The Broken Sword came out in 1954, the same year The Lord of the Rings hit shelves. The two books share some similarities—both authors were influenced by their love of Norse mythology; both have a number of songs, though Tolkien’s were his cultures’ entertainment and Anderson’s was a way of working magic; both depict a war between good and evil in the realm of faerie; and for an American, Anderson’s novel has a distinctly British feel and British setting. But while Tolkien was interested in creating a new mythology, influenced as much by classical myth as by redemptive suffering and the industrialized slaughter of trench warfare, Anderson stuck to the source material. Tolkien was willing to give his novel an uplifting ending, redemption after the sacrifices the characters must make. Anderson does no such thing, and lets Ragnarök begin to unravel as the pages fly by.

The writing is flowery, but I think it has the same feel to a Norse translation from the same time period—a sweeping grandeur thanks to the antiquated, though brilliant, language. The novel underwent substantial revisions in 1971, which demystifies its purplish prose; while it does tighten up the story, lower the word count, and make the work more accessible to those allergic to faux-medieval argot, I think it loses some of its vibrancy and style in the process. That revision also reverses the story’s portrayal of religion as a background force. Both editions depict the old religions as they’re supplanted by the “White Christ“—the Norse Æsir are still commanding the chess-board and manipulating the pieces, but Anderson hints that their time will end as did the fading Tuatha of Ireland, and the war between elf and troll cripples both their races. The revisions removes Christianity as an active influence, and instead makes a fascinating switch that increases the Æsir’s manipulations. While I like the shifting focus on religion, overall I think the revisions weakened the story.

The Broken Sword takes no prisoners, and despite the merriment in its prose and vigor in its swordplay, it’s an unrelenting and stark novel. That makes it a unique fantasy novel for its time, entrenched in the grim apocalypse of its source material. Indeed, most of the novel’s flaws can be attributed to Anderson’s adherence to the same structure as Norse myth—the ending is the kind of abrupt halt found too often in old translations of sagas—and while I enjoyed its rustic prose, other readers may not be endeared by it. Still, I very much enjoyed The Broken Sword and would recommend it to anyone who loves a good pre-Tolkien fantasy, particularly if you’re after a viking adventure in the vein of Haggard’s Eric Brighteyes or Eddison’s Styrbion the Strong. And if you enjoy this one, Anderson wrote a number of similar stories.

The Broken Sword takes no prisoners, and despite the merriment in its prose and vigor in its swordplay, it’s an unrelenting and stark novel. That makes it a unique fantasy novel for its time, entrenched in the grim apocalypse of its source material. Indeed, most of the novel’s flaws can be attributed to Anderson’s adherence to the same structure as Norse myth—the ending is the kind of abrupt halt found too often in old translations of sagas—and while I enjoyed its rustic prose, other readers may not be endeared by it. Still, I very much enjoyed The Broken Sword and would recommend it to anyone who loves a good pre-Tolkien fantasy, particularly if you’re after a viking adventure in the vein of Haggard’s Eric Brighteyes or Eddison’s Styrbion the Strong. And if you enjoy this one, Anderson wrote a number of similar stories.

Thanks to Open Road Media and Netgalley, who provided an e-ARC in exchange for an open and honest review. (I should also note that the digital version they’re releasing on 30 December 2014 is the 1954 original edition, with the baroque/ostentatious prose.)

This sounds great Yours is the second review I’ve read lauding it. I’m going to have to pick it up. Great review

LikeLike

Thanks! I very much enjoyed it, I hope you do too!

LikeLike

That’s really cool that you read both editions. I really hate it when I read something and later discover it’s been tampered– er, I mean, revised.

My experience with Anderson is that his books are too short for his big ideas, so the tale always seems unsatisfactory. Is that the case here?

LikeLike

Yeah, I’m always leery of revisions—they’re rarely as good and lose some of the original’s magic. I have both editions and was flipping back and forth at times, but the 1971 revision felt so lifeless in comparison that I stopped checking it after a while.

Maybe it’s different viewpoints or reading different books, but I haven’t noticed that about Anderson’s novels—for some of his short fiction I’d say yes. Well, I take that back… people love The High Crusade but I found it unsubstantial and boring as hell. I didn’t find that to be the case here, but I’ve noticed Norse sagas can just kinda end without any denouement, and Anderson followed suit.

LikeLike

Funny that you mention The High Crusade because that’s exactly what I meant. That, and The People of the Wind. Both might’ve been better with an extra 200 pages devoted to character development and suspense.

My next Anderson is Fire Time, and I have no idea what that one will be like. I was just hoping I’ve stumbled across some unusual Anderson duds.

LikeLike

Heh, I just saw your review of The High Crusade. It was the first Anderson novel I read. I didn’t try another one for six or eight years.

I can’t comment on Fire Time (or People of the Wind) but I see it’s pretty well-rated on Goodreads. Hoping it turns out to be a better one for you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m quite a fan of The Broken Sword as well. Anderson also did some direct translations of Norse sagas and they’re worth checking out. And they’re very grim!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ll have to keep an eye out for those—was unaware, thanks for the tip!

LikeLike

Pingback: Appendix N: The Broken Sword by Poul Anderson | Logic is my Virgin Sacrifice to Reality