Tags

You might have noticed I haven’t been posting as much SF recently; soon enough, I’ll have something to make up for that. My summer project is to start reading all the science fiction and fantasy magazines I’ve ended up with. (Along with reading novels and anthologies, of course.)

For a few years now, I’ve been amassing SF magazines without a conscious decision to collect them. Once at a library bag sale I stuffed a few in as filler; another time I bought a bunch of crappy ’70s ‘zines from a used bookstore since they were only a dollar per; a friend who was moving left me with some issues of Amazing and Omni. I bought some Worlds of Tomorrow off eBay since they had Philip K. Dick stories in them and nobody bid against me. Etc. What triggered me to start collecting on a serious basis was picking up some issues at the local flea market; well, I had to buy some more issues to complete the serials included in what I just bought, which lead to some bulk lots on eBay, which lead to more serials to complete, and now I’m sitting around wondering why I have so damn much musty old paper and where I’m going to store it all.

I’d been debating what to do about it—back even before my flea market find turned into a space concern—since there’s a difference between slogging through one giant post and by spending one blog post at a time to go over individual stories. At this point, I feel I may as well read and review them on an issue-by-issue basis. My primary inspiration was Rich Horton’s series of retro reviews over at Black Gate, which has touched on the magazines in the same kind of way I was thinking of; so far, only 2-3 of the Galaxy issues I own have been reviewed, along with one of F&SF. That means reviews around 2x-3x what I normally post, so we’ll see how it goes.

What I like about them is that they’re more primary source documents—an anthology or omnibus collects the stories, but it lacks, for example: the letters column, editorial, book review section, the ads, the whole general feel of the genre (by way of the magazine) to put things into context. Plus, if you haven’t noticed by now, I don’t mind rooting around in the dustbins of history in the hopes of finding some forgotten gem, and there are boatloads of stories which have never been reprinted outside of their magazine of origin. (And others which have been in constant reprint, and this saves me the effort from tracking down each collection.)

I wouldn’t say that I have an exhaustive selection, or even an impressive number of issues, but it is a decent spread:

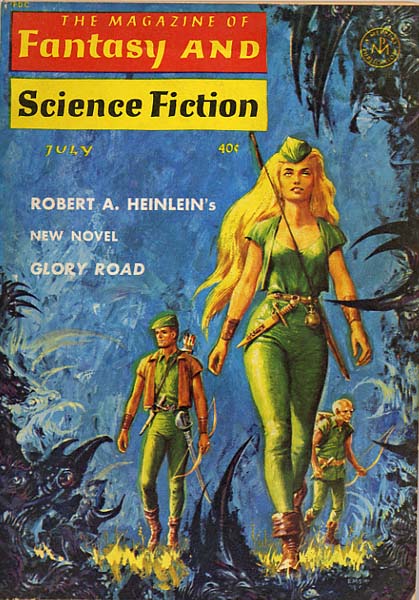

- a sizable chunk of F&SF from 1954 to 1980, centered on the ’60s

- a slice of Analog from ’65-’67 and ’71, some from the early ’80s, and a handful from the mid-’50s when it was still Astounding

- a small run of Pohl’s Worlds of Tomorrow from ’65-’67 and Worlds of If from its Hugo winning years (including a complete set of 1968) on to its end in 1974

- some Amazing and Fantastic, mostly from the Cele Goldsmith-Lalli years (1958-1965), as well as Fantastic in the sword-and-sorcery ’70s

- and the centerpiece of the collection, a pile of early-years issues of Galaxy, as well as some issues showcasing the hot mess it became in the ’70s.

On top of that, some smaller mags such as Original Science Fiction, Imaginative Tales, Asimov’s Science Fiction, Infinity, Fantastic Universe, and a few pulps, including Planet Stories, Startling Stories, Thrilling Wonder, and Ray Palmer’s sensationalist Fantastic Adventures. Plus some digital copies, from sources like the Internet Archive, the Pulp Magazine Project and Project Gutenberg.

What that means is a lot of fiction from a lot of authors: Asimov, Bester, Bradbury, Dick, Herbert, Matheson, Vonnegut, Silverberg, Jack Vance, Fritz Leiber, Walter M. Miller, Larry Niven, Joanna Russ, James Tiptree Jr., Leigh Brackett, Brian Aldiss, Lester del Rey, Frederic Brown, Frederik Pohl, Gordon R. Dickson, Eric Frank Russell, A. Bertram Chandler, Manly Wade Wellman, Mack Reynolds, Randall Garrett, Poul Anderson, Philip Jose Farmer, Damon Knight, Robert Sheckley, William Tenn, Thomas M. Disch, J.G. Ballard, Harlan Ellison, Bob Shaw, Barry Malzberg, Fred Saberhagen, Michael Moorcock, Gardner F. Fox, L. Sprague de Camp and Lin Carter. A good run from legends like Ed Hamilton and A.E. van Vogt down to new blood like George Alec Effinger, Timothy Zahn, and Glen Cook.

And, a good number of serials, from Avram Davidson, Poul Anderson, Mack Reynolds, Keith Laumer, Jack Williamson and Frederik Pohl, C.J. Cherryh, Alexi and Cory Panshin, Colin Knapp, Philip K. Dick, Roger Zelazny, two by John Brunner, several by Clifford Simak, and at least one Robert Heinlein. (Two if I can track down just a few more issues…) I’m planning on reviewing those in their book form in shorter posts, since I hate the idea of divvying up reviews by halves or thirds since it leads to spoilers.

Format

The two main formats of science-fiction magazines were pulp and digest, neither of which really exist any more.

The pulp format was most popular between the 1920s and the mid-1950s; depending on the publisher and period, a pulp would be roughly the same size as a modern graphic novel trade paperback at 6 ⅝” × 10 ¼” (give or take an inch, since some magazines, like Startling Stories, were often over an inch shorter than others). Instead of high-quality slick pages like a graphic novel trade, pulps were made up of the cheap wood-pulp paper that gives them their name: rough-edged, miscut, often covered in perforations or other imperfections based on the paper vendor used that week. And, with its own distinct smell due to age and deterioration The magazines had varying page counts: 128 pages was the norm, but a SF pulp could easily clock in at 160 pages or more. That made them half-an-inch thick on average, but cheaper paper (or larger page counts) could increase that to almost an inch. Because that big size took up a lot of retailer shelf space—and because the rough-edged, cheap-papered pulps lacked a certain post-Depression/post-War finery—they were slowly edged out and replaced by the digest size in the early 1950s.

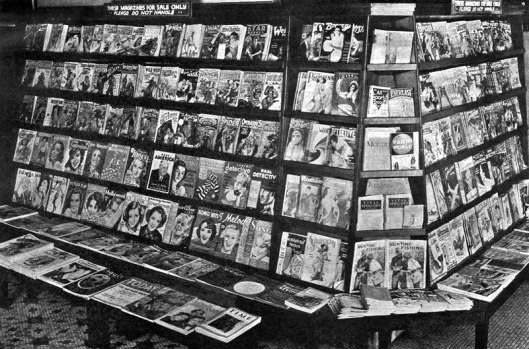

Pulp magazine and news stand, May-June 1935. Westerns and mysteries reign, though I can spot Weird Tales, hero pulps The Spider and Operator #5, and a number of aviation titles.

The digest format was particular to genre fiction magazines from the ’50s to the ’80s, as most other magazines used the standard slick size, or moved there by the 1990s. Reader’s Digest and Bird Watcher’s Digest are probably the most famous magazines still using the format, though TV Guide used it until the early 2000s. Slightly bigger than a paperback book at around 5 ½” x 7 ½”, and clocking in between 130 and 200 pages, a fiction digest gave around the same amount of text as a novel for a lower price. Astounding Science Fiction jumped to the digest size in 1943 due to wartime paper shortages; it was a prophetic move, because there was a mad rush of science fiction digests in the early ’50s after the popularity of Galaxy (1950) and F&SF (late 1949). Digest was also the standard format for most other fiction magazines of the era as well: Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, Alfred Hitchcock’s Mystery Magazine, Manhunt, et al, though most of them switched format by the 1970s. F&SF and Analog survive today, still in the digest format; just about every other magazine died off or moved to the standard slick size.

Magazine stand, Sept 1954. The end of the pulp era, and the digest format is really taking off; I can spot Fantastic, If, Imagination, and several other SF mags on there. Also, check out the inclusion of paperbacks on the right.

There were a few other SF magazines published using the bedsheet-size format, which would be around 9 ½” x 12″ in size. The iconic Life magazine is probably the best-known bedsheet magazine. In the SF field, Analog drifted to bedsheet size in 1963-65; the original Amazing Stories was bedsheet size, as was Gernsback’s later, short-lived Science Fiction Plus. I don’t own any of those, in part because they cost so damn much, though I’ve always been interested in going after them. Omni and a few other magazines (the attempts to re-start Amazing Stories, for one) used the slick size, which would be the standard high-gloss magazines you see in your doctor’s office like Travel, Time, Car and Driver, Outside, Rolling Stone, et al.

Fiction

The shortest stories fit for publication would be poems/verse, but after that would be the short-short: any story under ~2,000 words. It’s seen a modern revival in the form of flash fiction, stories under ~300-500 words. Of course, there’s only so much you can fit into a micro-narrative, so it’s more for a single punchline than a meaningful plot.

The average short story will fall anywhere up to ~8,000 words in length—long enough for an established narrative, and good filler to stick between the issue’s novella or serial. Both the Hugo and Nebula awards draw the line at 7,500 words.

The next step up would be the novelette—a story still not yet a novel, but long enough to have chapters or other breaks to offer more development and tension before the climax. At this point, it’s a dead format, considering that a novelette is brief and insubstantial. The Hugo and Nebula awards gauge a novelette as any story between 7,500 and 17,500 words, though other sources will place them as anywhere up to 20,000-25,000 words.

The largest form of fiction that can be published in one single magazine issue would be the novella, or the short novel, which is an accurate description. The novella is a full novel in everything but length, and includes chapters, a full story arc, a complex plot, and plenty of detail. Another art form slowly becoming extinct, the novella was a good choice for many authors in the ’50s-’60s; they could market it to the magazines first, then polish it, expand upon it, and have the lion’s share of a book already ready-made. Novellas are typically over 15,000 words in length; the Hugo and Nebula requirements are for fiction between 17,500 and 40,000 words in length.

Many magazines would proclaim that between its covers was “A Full Novel” of some sort or another; usually these works would be 25,000-75,000 words in length, though some pulp magazines would call stories as short as 10,000 words “full and complete novels.” It’s also worth noting that a true full-length book novels back then could easily end at 50,000 or 80,000 words, where today’s reading preferences for fantasy and science fiction pushes for works closer to 100,000 or 120,000 words in length, plus sequels.

Of course, there’s also the potential that an author—especially a popular one—would write something that was a bit longer than, say, the 35,000 words you had space for. Or maybe an editor would have the complete contents of a hardcover novel before its book publication. In that case, the editor would opt for serialization; for the digest format, that meant splitting the story into half or thirds to spread out publication. In the pulp days, running overlapping serials at once meant that divvying them up by sixths or eighths would keep readers going, get them addicted on another serial being printed in the same issue, and keep circulation soaring. Frederik Pohl used that strategy with Galaxy and Worlds of If, staggering starts, middles, and endings of two or even three solid serials per issue.

Most issues of a magazine will include one novella or serial installment per issue, a novella and a novelette or two, or several novelettes, along with a number of shorter works to finish out the page count. Standard features of a SF magazine would be the editorial, book review section, and letters column, but a few other types of article would crop up. A few magazines, specifically Imagination (“Fandora’s Box”) and If (“Our Man In Fandom”), included a look at the fan community and the numerous SF fanzines being published. Most of the “serious” magazines—e.g., Astounding/Analog, Galaxy—would publish science articles. And a little project by Isaac Asimov to help him prepare for his doctorate led to the creation of the “non-fact” article, a scientific-style article on a fictional item or idea.

Magazines are frustrating. So many of the stories were turned into novels and drastically changed….. I dunno, I often feel like reading only what stayed as shorts in the magazines and avoid all serialized novels (as you point out). So that’s the reason my personal collection of magazines has remained small and unread. I know they contain lots of short stories that were never published in collections that deserve to be read…

LikeLike

Yeah, I know what you mean. The serials in particular I’ve been kind of counting as a bonus and not as a focal point; the genre historian in me would love to do some compare/contrasts with how the shorter fiction emerged into novel form. I don’t have the time or incentive to do that, though, except with books I’ve already read. But I’ve read enough Ace doubles and DAW books expanded from novellas to know that most of the time, you’re really not gaining anything meaningful with the added content. (I actually prefer the novella version of Hawksbill Sation for instance; it lacks the flashbacks to future-Earth, ergo the misogyny, and felt like a tighter story to me.)

Plus, some magazines editors trimmed down serials to make them better reads—I remember Heinlein in particular complaining in a forward about how Fred Pohl “eviscerated an earlier serialized version of this work” or something like that, for one of his more excessive later-years novels. (I think it was for Farnham’s Freehold, and most of the cut content was from the boring first act.)

On the other hand, I’d rather read the expanded and polished final novel rather than the rough and shortened first magazine draft. We’ll see how it goes.

LikeLike

Even if they’re “better” in that format I rather read something with slightly less editorial control — I rather read something more along the lines of what the author wanted to write… But then again, they could be asked by their publishers to make their stories longer and then indulge in padding…

LikeLike

To be honest, I don’t think any form of publishing allows for pure authorial freedom… maybe self publishing *shudder*… or blogging, haha.

It really just depends on which editor you’re dealing with for which publishing outlet. And how well established you are in the field, which gives some weight to throw around when it comes to authorial control.

LikeLike

Hi there.

I heartily applaud your resolution to get to grips with your collection and do some mega-serious reading.The very best of luck and … don’t strain your eyes.

All the very best.

Kris

LikeLike

Thanks! I’ll try to avoid the eyestrain, haha.

LikeLike

Sounds like you’ll have a blast! And don’t forget all those covers!! Loads of great art from the top sf artists of the day.

A minor good thing about having runs of magazines (unlike my paltry pulp collection, which is author specific) is that letter column comments, etc. on stories run a couple of issues behind the story’s appearance, and you’ll be able to read them as soon as you finish the story if you want!

Mike

LikeLike

To be honest, the covers were a driving incentive to keep buying the things—haha.

Definitely a good point about the letter columns; I’ve skimmed a couple from the magazines I have solid blocks of (If and Fantastic in particular, since they actually had letter columns) and it’s neat to see some of the ongoing discussions that the magazines, stories, articles, or other letters generated.

Which specific authors are you collecting? I’ve done a lot of selecting based on authors as well, especially for some of my favorites (Brackett and early Bradbury in the Planet Stories, Poul Anderson, Alfred Bester, etc.), but also some of the rarer authors who didn’t publish as many novels or collections… After reading Greener Than You Think and The Long Loud Silence, I went after issues with Ward Moore or Wilson Tucker stories.

LikeLike

Perhaps some of the more famous authors late in their careers did — I mean, how else would Heinlein get his later, self-indulgent, elephant-sized tomes (of crud) published? (i.e. The Number of the Beast, The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, I Will Fear No Evil, etc.) haha

LikeLike

haha yeah, that’s especially true for modern authors. After the third or fourth book in your megaseries, you pretty much have free reign to write whatever you want because editorial control interferes with the publisher’s license to print money… that did as much to drive me away from reading fantasy as the dull, repetitive plots and cookie-cutter worldbuilding. I think later Heinlein would have been made…well, readable… with more editorial input. Or at least someone standing by to say “Hey Bob, maybe this isn’t the greatest thing ever.”

LikeLike

I was specifically collecting first magazine appearances by Jack Vance. I have most of them but stopped a few issues short of completeness years ago for no particular reason. I expect I could fill in the gaps fairly easily these days.

Originally it was a fairly cheap way to collect him, but of course his books started coming out first as limited edition h/cs, so I was lured into collecting them as well… Completting a couple of gaps there would cost serious money! But I guess between magazines, paperbacks and hardbacks, I have the bulk of his stuff two or three times over by now…

Mike

LikeLike

I can imagine; Vance has been getting more attention these days from those limited ed collections. I’d hoped to pick up some of those Vance editions by Subterranean but as soon as they go out of print, they start selling for double their MSRP, which increases accordingly with demand. I can imagine people going after the original magazines could cause a price spike there as well.

Vance is one of my favorites; a lot of material to go through as well, given how prolific he was.

LikeLike

Hmm, maybe I shouild dust down my ‘want’ list and go hunting! Of course, some of mine may not count as true first appearances as they’re in UK editions of the magazines but I think you can take some things too far, so I’m not aiming to correct that minor hiccup!

And I managed not to subscribe to the VIE, which was an all-or-nothing deal for 46(?) leatherbound volumes!

Mike

LikeLike

Hey, a first printing is still a first printing. Close enough for government work!

I am in love with the concept of the VIE, but that’s definitely something outside my price range… but I’ll keep buying these old books and magazines containing Vance stories.

LikeLike

Pingback: 2013 In Review | Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased