An interesting little historical footnote. Back in 1950, science fiction was still trying to discover itself as a serious genre, and lay split between John Campbell’s school of Astounding (e.g., harder science fiction with slight social commentary or prophetic content) and a swath of throwbacks from the ’30s and ’40s trying to evolve from “western in space”-style space opera, with bug-eyed monsters and robot menaces (mags like Amazing Stories, Planet Stories, Thrilling Stories, and Startling Stories).

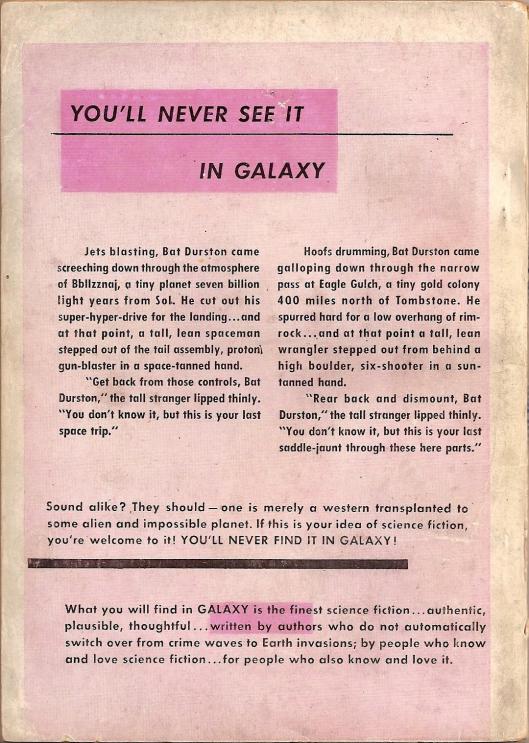

The first serious competitor to Astounding‘s dominance was Galaxy, which focused on harder SF that doubled as social satire (its first editor, Horace L. Gold, loved him some stories that mixed Twilight Zone-style shock endings with comedic real-world commentary). While Campbell gave SF a heart by demanding his writers consider the human side of their stories, Gold gave SF a mirror to humanity—he gave it a soul. And right from the first issue, with the back cover above, the magazine carved out its own niche in the genre; in its early years it featured such classics as Ray Bradbury‘s “The Fireman”, later expanded as Fahrenheit 451; Robert A. Heinlein‘s The Puppet Masters; and Alfred Bester‘s The Demolished Man. Galaxy (and later editor Fred Pohl) would go on to a very successful run up through the ’60s, though the magazine lost steam and by 1979 was a shell of its former selves.

It’s an interesting footnote in a greater paradigm shift in science fiction; the world had been awed by atomic power and other new wonder devices that emerged in the post-war boom, and with start of the the Space Race looming just seven years in the future, science fiction was looking more towards fiction inspired by known science and not space western escapism. Along with Astounding (later Analog) and magazines like The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, the digest magazines were moving the genre towards a more serious, more intelligent use of SF. Certainly, not every story published in those mags was smart, savvy, or tastefully done, but they latched onto Campbell’s school of SF and developed it, molding it into the genre we know today, and moving it out of the pulp ghetto and into a realm where it’s at least somewhat socially accepted.

Of course, the ’50s SF trend isn’t without faults, otherwise the New Wave of the late ’60s and ’70s wouldn’t have come around to deconstruct it. The biggest problem I have with it is the pompous, self-aggrandizing elitism that came along with SF’s newfound respect. I can point to a number of editorials, introductions, and articles by people like Campbell and Heinlein, meandering on about how SF is the hardest genre to write in because of its rigid scientific accuracy, how it is every genre in one, how it’s the genre which all fiction of the future will become, how stressful it is to write something both entertaining and prophetic. You can still see shards of this elitism in Hard SF today. And to be honest, a lot of the stuff published in these old magazines seems pretty ordinary and uninspiring today; formulaic, rigid, unimaginative. I’m not quite sure what those old Golden Age stalwarts were chest-beating about.

I lost my point somewhere in there. In essence, this little back-cover blurb to Galaxy #1, October 1950, fascinates me for its place in the genre’s history. It’s not a lynchpin or Jonbar hinge of any kind, but it does reflect the paradigm shift taking the genre away from pulp space opera to the pseudo-literary digest magazine SF of the ’50s.

Of all the sci-fi magazines I want to collect (I don’t own a single one at the moment) Galaxy and New Worlds are at the top of my list….

LikeLike

I actually own a few copies of Galaxy, picked up for a dollar each at a used bookstore. Most from the late ’70s, during the magazine’s decline, and all of the serials I’ve already read in book form (Cherryh’s first Faded Sun novel, and Pohl’s underwhelming Jem). Some of the shorts are interesting, tho, I should read and review them some time.

Not sure I’ll ever own any New Worlds issues, but I’d certainly love to.

LikeLike

Yeah, it seems difficult to find any magazines earlier than the late 70’s at used bookstores. My university library recently had a cool display case filled with 50s pulp, and a sign urging readers to come check out their special collections – but I don’t just want to look at it; I want to take it home.

LikeLike

There are a few bookstores in my area with lots of pre-’70s magazines, lots of ’50s digests and even some pulps going back to the twenties. But anything before the mid-1960s starts costing an arm and a leg. I wish there was an easier way to digitize, distribute, and preserve them, because $60 for some moldering old paper is way out of my price range.

LikeLike

$60 is definitely steep, but I would love to find some place here in St. Louis where I could browse some of them.

Have you seen the Pulp Magazine Project? It’s not huge, but they’ve got a bunch of high-quality PDFs.

LikeLike

Great find! I actually like science fiction that plays around with Western tropes. Many of Heinlein’s Future History stories are an interesting take on the idea of a frontier and the kinds of people who go there to build humanity’s future.

But of course there was a ton of bad transplanted horse opera, inferior to Burroughs’ Mars stories of C.L. Moore’s Northwest Smith series. It’s easy to see why Galaxy would want to distance itself from that.

LikeLike

I like the idea of fusing the genres as well; there’s some distinct similarities they share: brave and resourceful pioneers pushing back the wilderness of the frontier, etc. And when they’re mashed up, it’s pretty entertaining… then again I’m a big Firefly fan.

LikeLike

Well, most of the volumes of New Worlds go for 6 or so dollars on Marx books. Again, for people in the US it’s super cheap.

Some of the Galaxy editions are 1 dollar….

http://www.marxbooks.com/index.php?startpos=1&action=Magazines&rec_per_page=50&title=GALAXY

LikeLike

The best examples, in my mind, of the SF and Western genres do bear a commonality, though: Both the mythic “Wild” West and the setting of (insert name your favorite SF work here) are places-other-than-our-own that serve as a mirror to our own place and time, a way to comment on such without directly criticizing/referencing it. I can understand the motive behind the “Bat Durston” blurb — you don’t want to simply replace the horse with a spaceship, the six-shooter with a “proton gun-blaster” and call it a day because that’s lazy — but the best practitioners of both genres would each recognize and respect what the other was trying to do.

LikeLike

Definitely, I think that’s the benefit of fiction in general—it can expose the truths of the world by mirroring it in a fake, larger-than-life setting.

The blurb is a bit blunt—heavy ’50s elitism there—but I always saw it more attacking the lowest of low-brow schlock writing, and authors who “jumped ship” between genres by churning out the same story and filing off the serial numbers to fit one genre or another.

Not something I personally have a problem with—writers have bills to pay too—especially since I think the western frontier and the final frontier have enough similarities to make overlap fascinating.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Year’s Best S-F: 5th Annual Edition, ed. Judith Merril (Dell F118 – 1961) | Vintage (and not so vintage) Paperbacks

Pingback: Judgment Night – C.L. Moore | Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased