Tags

1930s, 1938, alternate realities, Astounding Science Fiction, Ed Emshwiller, invasion!, Jack Gaughan, Jack Williamson, pulp, Pyramid Books, science fiction, time travel

I’ve read a lot of serious, cerebral, “thinker” SF books of late. And I need a break, something fun and mindless. The Legion of Time‘s been waiting near the top of my stack since I picked it up, as part of my “one time-travel book lead to another” venture in SF research. It’s one of Jack Williamson’s old pulp stories, an Astounding Science Fiction serial during May-June-July of 1938. The last I read of Williamson were the underwhelming Reefs of Space trilogy. Part of the problem there could be my apathy towards his co-writer Frederik Pohl, so I’m willing to give Williamson another shot; his ’30s pulp stories are often pretty good, providing you’re not put-off by pulp’s sketchy science, and hit-or-often-miss prose.

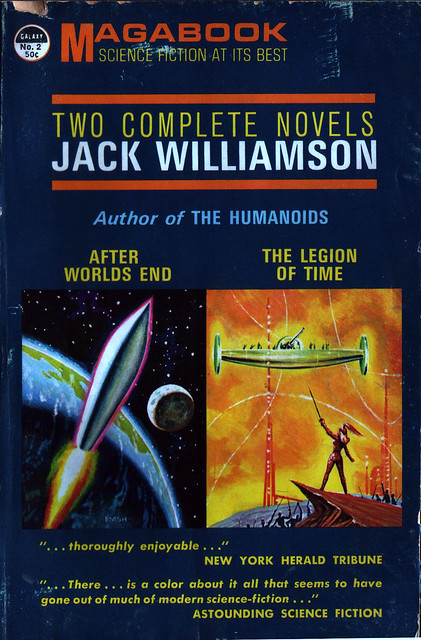

Galaxy Megabook #02 – 1963 – Ed Emsh. Galaxy briefly tried its hand at the double format; there were only three of them, each the same digest size and shape as Galaxy magazine.

The unfortunately named Denny Lanning, college student, is approached by two beautiful women, each from an alternate future of Earth. As it’s explained to him as a simplified allegory by the bright beauty Lethanee, dumbed down for his primitive human brain:

The world is a long corridor, from the beginning of existence to the end. Events are groups in a sculptured frieze that runs endlessly along the walls. And time is a lantern carried steadily through the hall, to illuminate the groups one by one. It is the light of awareness, the subjective reality of consciousness.

“Again and again the corridor branches, for it is the museum of all that is possible. The bearer of the lantern may take one turning, or another. And always, many halls that might have been illuminated with reality are left forever in the dark…

“You, Denny Lanning,” she went on, “are destined, for a little time, to carry the lantern.

Only one of two warring futures can exist, and the actions of mortal men will determine which will exist and which will fall into nothingness. On one side is Lethonee, representing idyllic Jonbar, a land of towering spires and wide, green boulevards. On the other is Sorainya, dark mistress of Gyronch and its bleak, dead-end future. Good and evil, with room for only one of them to become Earth’s real future. And Denny will soon be the lantern-bearer, the determiner of fate.

According to the rules of time and space, he can only be plucked from his time when he’s near death—as luck would have it, he’s a combat journalist dedicated to fighting tyranny, so after many years of wandering, he gets shot down during the Chinese Civil War. Together with his old college roommates, including his dead best friend and a genius tortured by Sorainya, Denny becomes part of the titular Legion of Time: dead and dying soldiers plucked from World Wars both recent and yet to come. Aboard their timeship Chronion, they will fight against Gyronch and its armies of fighter-slaves—bred from bio-engineering humans and ants, like the Myrmidons of yore.

Their mission is the penultimate butterfly effect: a boy in the Ozarks will come to a Jonbar Hinge, and must choose between picking up a magnet or a pebble. If he picks up the magnet, it’ll trigger a life-long interest in science, which will result in the serene future utopia of Jonbar. If he picks up the pebble, it’ll lead to him breaking windows or killing birds with it or something, culminating with the despotic tyranny of Gyronch. Sorainya, of course, has stolen the magnet, and it’s up to our brave heroes to return it.

Sphere – 1977 – illo by Bob Layzell. Battle of the timeships!—the Chronion bombarded by the Gyronch vessel.

Williamson’s acute prophecy depicts an upcoming World War II, and even pins down the Battle of Paris to 1940. (Of course, in 1938, these kinds of predictions were more “when” than “if” another World War would break out.) The Legion of Time acts as a prophetic allegory for the upcoming clash. During his war-reporter stage, Denny writes books hoping to show “that the world is nearing a decisive conflict between democratic civilization and despotic absolutism,” reflecting not just the the future time-war between Jonbar and Gyronch, but the events within Denny’s fictional time and Williamson’s real one. Denny reports on many of the inter-war conflicts, even joining in at points, always serving on the side of the underdog against the oppressor; he’s very Hemingway-esque.

But that clear-cut, black-and-white morality doesn’t apply to the varied characters: Gyronch is the future of dead-end tyranny, and anyone fighting against it is on the side of peace and democracy. This idealism—and that of a multinational fighting force recruited to fight for Jonbar—is the unadulterated idealism of early science fiction writers; it reminds me of Gene Roddenberry’s Federation and Asimov’s benevolent robots. I love the concept; you’ve got to admit it, pulling dying men out of the World Wars like futuristic Einherjar to fight for vying realities is a good one.

There’s no sliver of reality in sticking RAF fighter aces, Prussian gentry, American protagonists and Russian rocket-flyers, allies and old enemies, together as a functioning fighting force. But stoic reality is not the point. The plot’s about a magnet of destiny, over which dozens of characters die fighting a villain who these men can’t hurt because she’s so beautiful; trust me, it’s really not the point. Juvenile, yes. Fun, also yes.

Williamson is not an award-winning writer, though his purple prose lends itself well to a fast action tale. Legion is the same vein of romantic science escapism as Burroughs or A. Merritt, tales of fantastic adventure tied to the SF genre by a thin cord of SF tropes and the loud incantation of techno-babble. Williamson’s prose is very Merrittesque, similar in its adventurous tone, swashbuckling action, and a beautiful femme fatale—no less than two of the latter in this novella. (Williamson began writing SF after reading Merritt’s work.) The story’s strengths are its creative use of time-travel and its intense escapism, making for good lighthearted reading.

The characters, of course, are less than two-dimensional. Most of them speak Ethnic Stereotype, so you have the fast-speaking little Spaniard, and a number of stern Germans going “Ach!” and “Himmel!” all the time. Denny Lanning is the kind of everyman character who should star in his own college melodrama, going up against some overzealous jock to win the heart of a pretty girl (and the football championship, etc.) at the last minute; as The Legion of Time starts in a college dorm, it peers at that trope for one strange moment. And you can see snippets of Williamson’s early influences and aspects of the novella’s serialization, such as the infrequent but dry exposition dumps, a repetition in relaying information while overstating the obvious, and the frenetic action see-sawing back and forth.

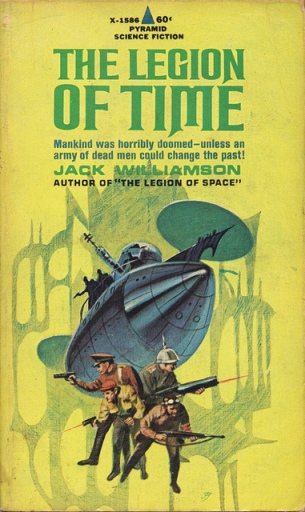

Pyramid Books #X-1586 – 1967 – Jack Gaughan. Dead soldiers and their flying submarines. This was cutting-edge in the ’30s.

A gleeful idealistic romp, as Brian Aldiss put it, The Legion of Time is “philosophically barren but a swashbuckling delight.” The plot and characters share the same depth and fortitude as cardboard, but most of Williamson’s ideas are impressive. And like most vintage fiction, I find it interesting to see how contemporary events influenced the novella (e.g., the theme of democracy versus fascism; a French colonel who died in 1940 fighting to save Paris). If you want a good example of pulp SF’s thrilling adventurism, The Legion of Time will work. It’s fast and furious fun, unburdened by complexity or subjective morality.

It’s not the best written pulp tale I’ve read; it’s predictable, shallow—predictably shallow—which is a general flaw with Golden Age pulps. You can see the stitches where the story was hacked into three serials. And the old-school techniques, such as the gee-whiz super-science and a pair of exposition blocks, won’t do much for readers with a modern taste. But the breathless prose makes the action jump, and some excellent core ideas make it a worthy read. It’s a fantastic choice if you want some exuberant pulp escapism. Worst case scenario, you finish it in a few nights.

Haven’t read this one yet. Just read and reviewed (review will be up i a few days) Williamson’s Bright New Universe (1967) — a desperate attempt to infuse a thought provoking strain of social commentary into a pulp framework.

This one has been on my list forever…

LikeLike

Looking forward to your review, Bright New Universe has been on my buy list for a while.

LikeLike

I’ve scheduled it to be published tomorrow morning. I felt that the attempt to integrate the social commentary into the pulp framework didn’t work, at all…. The black and white dichotomies so present in pulp don’t jive with the attempt to “complicate the picture” because he FORCES the social commentary to conform to a simple pulp framework….

LikeLike

I grabbed “The Legion of Time” in a bookshop in here in England in the 1950s, attracted by the artwork on the cover of the paperback more than anything else. It became one of my favourite novels and it still is. Yes, on the one hand it might be very silly (even a kind-of “Star Wars” romp in a time-travel setting?) but on the other hand, I found it just resonated with me and was immensely entertaining. I never forgot the axis round which the plot revolved, that someone could choose to pick up either a magnet or a stone lying close together on the ground, and the choice would decide the person’s future path. In 1960 I faced such a choice myself – should I quit college and get a job so I would have money, or should I go to university, remain poor for many years and study for a degree which might benefit me later in life? I chose the magnet, achieved a degree, and now I am retired and living in some comfort after a satisfying and well-paid professional life. Every day, I wonder what would have become of me and my family if I had picked up the stone instead. Small wonder, then, that I am still in love with this book!

LikeLike

Awesome anecdote. I loved the Jonbar Hinge concept, and it’s cool to see a real-life example, as it were. I can see why it’d resonate so much with you.

LikeLike

I am a sucker for all things time travel. I’ve got to try and find this one. Thanks for a great review. Do you have a list of good time travel tales? Thanks for the review.

LikeLike

Thanks! I thought this one and Fritz Leiber’s The Big Time made an interesting comparison. Silverberg’s Hawksbill Station was great. Tim Powers, Anubis Gates. I’ll see if I can think of any others.

LikeLike

Dinosaur Beach by Keith Laumer is an interesting take on a time paradox story: each civilization that discovers time travel finds that future civilizations are trying to edit and undo their mistakes and time-paradoxes.

LikeLike