Tags

1940s, 1942, 1950s, 1956, Astounding Science Fiction, Atomic Age!, Ballantine Books, Dean Ellis, Lester del Rey, Richard Powers, science fiction, super scientists, thriller

As fate would have it, my parents gifted me a bunch of science fiction paperbacks from a local dealer, including a copy of Lester del Rey’s Nerves, right before I posted my review of his Day of the Giants. So now I have an opportunity to dive into del Rey’s most important work. (It says a lot when his apex novel is one that hasn’t been reprinted since Three Mile Island was in the headlines).

Nerves takes place in an atomic processing plant and nuclear reactor; it wasn’t the first science fiction story to involve atomic power when it appeared in a 1942 issue of Astounding—there are hundreds of stories from the ’20s and ’30s featuring atomic drives, atomic rays, etc. But it was one of the first to take a serious, almost prophetic look at the future of atomic power… not as a super-science MacGuffin, but at its everyday applications.

It looked to be another normal day at the nuclear reactor in Kimberly, Missouri, but a surprise inspection throws off the daily routine. With everyone’s nerves on edge, there were bound to be a few accidents, which don’t go over well with the anti-atomic crowd. But the worst comes after the inspection has left. As a means to get rid of the newspapermen drumming up anti-atomic fervor, the plant’s manager scheduled work on a top-secret isotope—a backdoor deal for one of the visiting Southern senators, since the isotope’s designed to kill boll weevils. (In an age of using radiation to grow fruits and vegetables, I note the irony of radiation as a pesticide.) Needless to say… something goes wrong, and the plant’s crew struggles to clean up the molten remains of a reactor before it explodes. It threatens to destroy the United States. You know the drill.

The narrative jumps between three point-of-view characters. Doc Ferrel is the aging chief of the medical ward; he gets to deal with the many ailments which occur in the plant. Doc is our main character, and as such we see the disaster from the viewpoint of the infirmary, save for the few instances where Doc ventures out into the plant. Or we encounter our other PoV characters: Palmer, the manager of the plant; and Jorgenson, the cocky but brilliant engineer who was working on the isotopes when the pile went critical. All three are super-scientists of the Golden Age variety; hands-on, intelligent, and operating the everyday wonder devices of tomorrow.

Ballantine #151 – 1956 – Richard Powers. Just think, this one isn’t as surreal as Powers normal fare (such as the other cover he did for Nerves). I still like it.

Jorgenson snapped when the plant went up, seeing himself superior to the puny hoo-mans operating under him, but the others require his knowledge to fix the reactor. On the soft-touch side, there’s one chapter from the viewpoint of Doc’s aging wife, Emma, which gives a fascinating view of Kimberly as it reacts to the (unannounced) accident: a great sense of fear and foreboding there. Next, there’s several important supporting characters, such as rookie surgeon Jenkins undergoing his trial by fire, and Hokusai, a brilliant Japanese physicist (who has a “yellow peril” accent, but is otherwise presented in quite a positive light, considering del Rey penned the story after Pearl Harbor). Along with these, there are so many named but pointless characters who show up that it can be hard keeping track of the cast of thousands.

Coming three years before Hiroshima, the story was prophetic indeed… though del Rey misses out on a lot of marginal details. For example. The main point of nuclear reactors is to create “super-heavy isotopes” for use in medicine, science, and the military—a lot of MacGuffin isotopes that don’t exist. Power is secondary output, more limited in scope; I’m not sure this plant powers more than the one town. People are working in this reactor much as they’d work in a steel mill in Pittsburgh, up close and hands-on under layers of protective “armor” and in metal tanks (!). The main treatment to remove “radioactives” from the wounded is curare treatment (!!), and the use of other wonder-drugs like neo-heroin (!!!). We see some future-tech that just couldn’t cut it in the real world, such as prefab housing along the lines of the Dymaxion House and an abundance of sporty turbine cars. And the focus on medicinal characters makes the lack of triage—a product of World War II—disconcerting.

But I’m impressed by the amount of details he did get right, talking about nuclear piles and reactor cores, refining U-235, even the idea that nuclear reactors would become commonplace enough to power cities, and that people would protest against their potential dangers. The cleanup crews predate the liquidators of Chernobyl by some forty years with some striking similarities. The novel has its workers spending five minutes in the radioactive glow cleaning up the molten debris—five minutes their supervisors know are fatal. Compare Nerves with Frederik Pohl’s Chernobyl, for example.

Ballantine – 1966 – Richard Powers again. Ah, this one is suitably surreal. Perhaps too much so; the other one at least had visual ties to the novel.

I like seeing early conceptions of radiation, its uses and its hazards, from the era it came into fruition. And while the novel’s assumed science is far off the mark, it’s a wonderful illustration of the 1940s understanding of radiation. Again, the novel first appeared in the September, 1942 issue of Astounding, years before words like “nuclear” and “radiation” entered the mainstream vernacular. It was rewritten and expanded in 1956—the year the first commercial nuclear power station went into operation, in the UK. Previous nuclear reactors were experimental or operated by the military. So del Rey’s extrapolations are pretty damn impressive, since he couldn’t walk the corridors of a working nuclear power plant or watch a TV documentary on Chernobyl.

I’m surprised at how well-written Nerves is, though it’s far from perfect. It lacks the polish you’d expect from a modern thriller, which is what it’s purported to be, because of the writing style of its era. That would be the stereotypical Golden Age techniques which block attempts to generate tension: cliches abound; the dialogue can be stilted (hello, exposition!); technobabble increases as the plot progresses; the story’s sluggish because del Rey likes to over-explain various setting details. The tension it builds is pretty good, focusing on the cleanup and medical response to the disaster as well as the socio-political implications. And it’s competent and readable prose over the first three-fourths of the book. But the last quarter sags under the weight of technobabble and a confused, detached focus, unaided by its dated scientific theorizing.

Of course, I mentioned in my other del Rey review that his writing style, while competent and readable, isn’t flashy or interesting. It lacks depth and emotion, and lies along the lines of “workmanlike”—something that could be said of many Golden Age writers, so if that’s your preferred cup of tea, feel free to ignore this. The characters are interesting, if flat and lifeless, and there’s far too many named redshirts who show up once or twice and add nothing.

Astounding‘s editor John W. Campbell pushed for pathos and the inclusion of the human angle in the stories he bought, and del Rey has several running themes here: Doc’s ailing wife, the (albeit one-sided) nuclear reactor protests, the disaster and its after-shocks. But I wish the story wasn’t so clinical and detached, keeping a respectable distance from any depth.

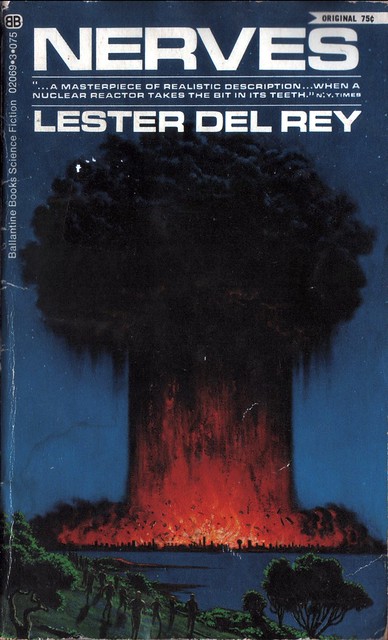

Ballantine – 1974 – Dean Ellis again. I guess there’s a law stating if you make one cover for Nerves, you have to make two.

Lester del Rey was a John W. Campbell writer, a Golden Age stalwart who didn’t quite make the transition from War era into the Space Age. And Nerves showcases that fact. It’s Campbell’s ideal story: populated with super-smart scientists; what was hoped to be prophetic science; the beneficial power of science and technology in everyday applications; and while del Rey focuses on the “human side” of the story, he does so in a dated and detached manner. As a time capsule piece, I thought it was cool to note the things del Rey got right, and the assumptions he got wrong. Nerves can be enjoyable, but it’s not exceptional; the style defeats its tension at the end, leaving it neither a compelling read nor a expertly crafted one. Worth looking into if you want a solid early look at a nuclear disaster, for people who love Golden Age novels, or for the SF completist.

This was one of those stories I really wanted to like, if only because other reviews have a tendency to tear it a new one for its faulty nuclear science. Given its age, and the knowledge of its era, I think del Rey did a good job on that front; atomic power wasn’t as advanced in 1956 as everyone seems to think, and its operation wasn’t well known by the general public. But this non-thrilling “thriller,” building towards a messy and slapdash conclusion, couldn’t rise to be much more than good/okay/average in my eyes.

SF completists and Golden Age fanboys might also be interested in comparing Nerves with Heinlein’s “Blowups Happen.” Again, lots of rocky pre-Hiroshima science, but there are some telling similarities—wearing heavy shielding to protect against “radioactives” for one. And this optimistic little cartoon from the same era reveals atomic knowledge of the early atomic age, a good comparison to del Rey’s novel.

I want this one…. The second Powers cover, sublime….

LikeLike

Cuff me, I prefer the first “arresting” cover of Ellis. Haven’t had the pleasure (?) to read a del Ray novel yet… and I don’t think I’ve come across any of his short work either. Stores here won’t have any–will have to pick one up in American this October.

LikeLike

Well, I like that one as well….

LikeLike

I don’t mind any of them. But I am kind of glad I ended up with the first one—“What are you reading?” *points to mushroom cloud on cover*

I’m beginning to think del Rey has been forgotten for a reason. His novels are pretty average; the short stories that I’ve read have been on par with the best of the ’40s-’50s (Sturgeon, Heinlein, Leiber, Walter M. Miller, etc.)… then again, those other authors were much better writing novels from the late-’50s on.

LikeLike

All the Lester Del Rey novels I’ve read have been of the juvenile variety — and poor at that…. What’s a good collection of his shorts?

LikeLike

I have Early del Rey; a bit rough and hit or miss at points, but a number are pretty good… Best Of Lester del Rey has worthwhile stories in it. “Helen O’Loy” is in most of the classic anthologies I own, and “Kindness” was well done.

LikeLike

“What’s a good collection of his shorts?” – maybe his polka dot shorts collection, but definitely not his undershorts collection. Umm, besides the bad joke, the short story collections are duly noted. *tips hat*

LikeLike

Pingback: Fantasy and Science Fiction. The human mind, our modern world. « E-Learning

Pingback: 3 Year Anniversary | Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased