Tags

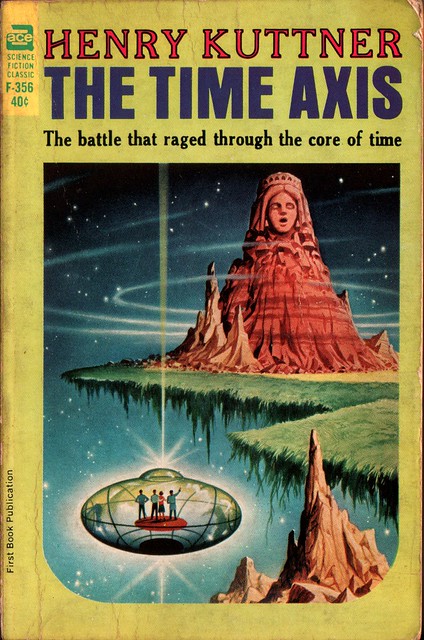

1940s, 1948, Ace Books, Alex Schomburg, Earle Bergey, far flung future, Henry Kuttner, pulp, robots!, science fiction, Startling Stories, super scientists, time travel

The whole thing never happened and I can prove it — now. But Ira De Kalb made me wait a billion years to write the story.

So we start with a paradox. But the strangest thing of all is that there are no real paradoxes involved, not one. This is a record of logic. Not human logic, of course, not the logic of this time or this space.

I find Henry Kuttner something of a tragic figure in SF because of how important he was and how forgotten he’s since become; a name that shows up in every “Best SF” collection through the ’60s, and rarely since. With his wife, fellow SF legend C.L. Moore, they co-authored a wealth of stories and novels under a legion of pseudonyms. Both emerged from the Lovecraft Circle writing weird fiction and horror, became the backbone that supported Astounding (in the form of five dozen stories) during the war, and after it, populated Startling Stories and Thrilling Wonder with full-length novels. Together, Kuttner and Moore dominated SF in the 1940s.

But Kuttner wanted more than the small glories that came with being a popular pulp writer; the husband-wife pair stopped writing around 1954 and went back to school, heading to USC to get their Bachelors in psychology. Kuttner was in the middle of his MA when he died of a stroke in his sleep in 1958. He was forty-four. Moore never returned to writing; her second husband considered SF beneath him, and forbade her from writing (and, later, from being honored as an SFWA grandmaster). Both have since slipped into obscurity.

The Time Axis is told from the first-person perspective of Jerry Cortland, a freelance journalist trying to escape his miserable past (and alimony payments) in Brazil. There, he’s attacked by a strange being of pure energy—negative energy—which burns his hand, and gives him a brief glimpse of clarity. This creature is responsible for a growing number of murders, and the burn victims seem to center around Jerry. He’s contacted by scientists Ira De Kalb and Letta Essen, who reveal some shocking developments. De Kalb stumbled upon a puzzle-box from the far future, which gives flashes of realization and foretells The Face of Ea, the last city on Earth, besieged by a nekrotic plague of negative energy. That’s the same nekrotic being that burned Jerry, and those around him. Which was released, by accident, when Dr. De Kalb first opened the puzzle box. Now, the plague of nekrosis is growing: and as it does, it eats away at the fabric of time itself.

Still with me? Yeah, it’s a lot to wash down… and that’s just the first thirty pages or so. Some more development before I start reviewing. So, it turns out De Kalb’s stumbled upon another great revelation: time isn’t a linear path, but is closer to a rotating sphere, and its axis is in the Canadian Laurentians. Hoping to learn more about The Face of Ea—and save all of time—they collect a Colonel who’s at odds with Cortland and journey to the future. (There are reasons for everything, I’m trying to be terse.)

But not far enough into the future; Cortland awakes to find his companions have new names, new memories, don’t recognize Jerry, and have had functioning roles in society for all their lives. For example, De Kalb goes by the name of Belem, and is a telepathic Mechandroid, a kind of cyborg; he’s in the midst of a revolt—Belem and other rebels are trying to make a Super-Mechandroid, forbidden by the authorities for obvious reasons. (Nobody likes machines that make even smarter machines.) Can Jerry figure out what the hell’s happening, pull the group together, and get the rest of the way to the Face of Ea? And if Cortland manages all that… can they stop the nekrosis?

I’ve looked far and wide, and I haven’t seen any evidence that this story was co-authored by Kuttner’s wife, C.L. Moore; most of their works were husband-wife collaborations. Which surprised me, since I saw little snippets of her fine imagery in the Swan Garden. Maybe her techniques were rubbing off on her husband? Kuttner has oft been described as a “competent, workmanlike” writer, which is a shame; the writing in Time Axis was better than “workmanlike”—Kuttner’s a better writer than Clarke or Asimov in my eyes—but Kuttner’s prose is straightforward and unexceptional for the most part, lacking in richness or texture. Seeing the occasional descriptive flourishes here made me think of Moore, not Kuttner, and if they are indeed Kuttner’s then I think I’ve underestimated him for quite some time. (If this was a collaboration—and given their writing tendencies, parts of it probably are—I wouldn’t be surprised; it’s one of their few that felt like two people had their hands on the wheel.)

If you haven’t guessed with all that setup, there’s a lot going on. This is a very complex work, almost frustratingly so; Kuttner isn’t too charitable with his explanations, and the novel could benefit from more clarity. Don’t worry, you, the reader, are not alone: protagonist Jerry Cortland is often overwhelmed by the science, the complexities, the sheer wonder thrown at him. A lot of the time, he doesn’t know what’s going on, and even when he gets explanations he isn’t given enough to work with. I feel for the guy, because I’m right there with him. The first thirty pages or so are De Kalb’s attempts to explain what’s going on; after all that, I was still a bit confused, and was overjoyed to find that Jerry’s response was essentially “What?”

(Kuttner was no slump at science—this book makes several uses of the Banach–Tarski paradox—but he had a thing for taking the science he wanted, and no more, and not letting known physics get in the way of a good story. So he’s not much of a Hard SF kind of guy. This novel is no exception, hence its dizzying array of quasi-scientific postulating.)

So, an unnecessary level of complexity; that’s a problem. Here’s another. After getting the plot to the time-axis so the characters can head forward in time… everyone arrives at the wrong point: only a few thousand years have passed, and The Face of Ea is nowhere near. I spent too long wondering how this related to the narrative I’d just slogged through; there’s no sense of linear progression, and feels like another story’s been dropped into the middle of this one. Having finished the novel, I can now say that it did matter, that it was worth it, it had some major impacts on the finale, it is not a bait and switch, and that you just have to soldier on until all becomes clear. (Or you could just give up, if the book isn’t your cup of tea.) I keep forgetting that Kuttner was a master of intricate plots; his ability to make a complex, creative story is unmatched.

There are plenty of times when Jerry/Kuttner says a concept or item is indescribable—the fantastic machine city, the language used by the future-men, the nekrotic monster—but unlike Lovecraft, he stops there. It’s annoying to find so many future wonders are incomprehensible, but I am glad that the indescribable isn’t described; it lets your imagination run wild, I guess, instead of tossing forth concepts that would have since became dated. Something I’m on the fence about, but it’s worth noting.

The Time Axis is a fascinating look back at Golden Age super-science-stories; it’s a big idea that can outdo all other big idea rivals, a book laden with frustrating complexities and wild, speculative creativity. It’s a good synthesis of science mind-blower and thrilling future adventure. But I can’t help thinking it could have been smoother, clearer, less Byzantine in its future pseudo-science. And I have a higher than average tolerance for SF not rooted in realistic science, which will annoy others. A good read? Yes, for the most part. A perfect book? Close, but no cigar; there were a few too many times where I wondered what’s going on, or where’s Kuttner going with this, or was otherwise drawn out of the narrative. When the book finally gets there, though, it’s worth it; the finale makes the entire plot rewarding.

From your review of The Time Axis, I suspect I’d get a bit bogged down in wondering just what was going on…

I feel that I should read more of his novels, but I tend to stick to his short stories; if you haven’t acquired a ‘best of’ collection, I suggest you do!

LikeLike

I was surprised at how obtuse the novel was, since the few reviews I’d read for it were glowing. To each their own.

I haven’t found any of Kuttner’s short-story collections—well, other than Robots Have No Tails—though I’ve read several of his short-stories in various anthologies.

LikeLike