Tags

1970s, 1980s, 1981, anthology/collection, Baen, dying earth, eldritch horror, fantasy, George R.R. Martin, Hugo Award winner, Nebula Award winner, psychological, science fiction, short fiction, weird fiction

There are two main factors that influence my book-buying.

First is the author. There are a lot of reputed authors who I’m drawn to, if only because they appear on best-of lists, or if other big-name authors name-drop them. Others are just authors I know and enjoy; my buy-on-sight short list includes a dozen authors. Including George R.R. Martin. Now, I’m something of a fantasy purist-elitist: I enjoy the genre, but I got sick of high fantasy dwarfs and elfs decades ago. Every once in a while I’ll pick up a fantasy novel, and nine out of ten times I end up disappointed; either it’s chock full of bad writing or the stock high fantasy dwarfs and orcs cliches.

So it should say a lot when Martin’s one of the handful of fantasy authors I have scant criticism for. (Most would be about the fact he writes one of those megaseries where plotlines are rarely concluded, and instead, more are heaped on with each book, to the point where the epic climax the first book promised will never occur as the author and his/her readers all die before it rolls around.) I’m a huge fan of his Song of Ice and Fire series, which I think is the best fantasy series printed thus far in my lifetime, even if it is the horrible long-running, never-ending megaseries contemporary fantasy appreciates. Martin has a beautiful writing style, and he can do some remarkable dark and horrible things to his protagonists. He takes the old adage “kill your darlings” to heart, and can cut such a bloody swath through his characters it puts every other writer to shame.

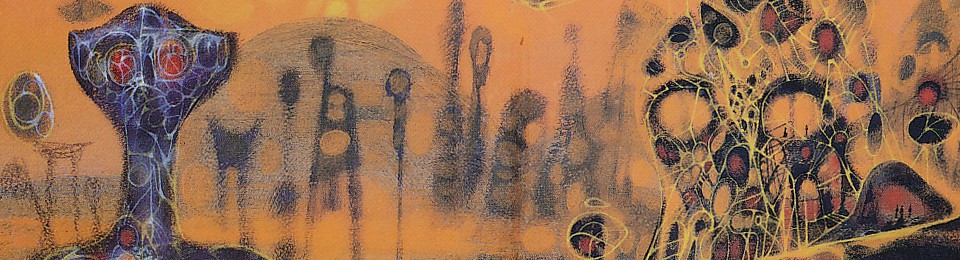

The second influencing factor would be the book’s cover. And look at this thing. The skull on there frames all the little bits, which include some roses, and coins, ancient ruins, something strange and fanged lurking in a darkened cave. Spiders and sharp bits and smoke. The skull’s bald shine-spot could be a desert plain or a burning sun or a clouded maelstrom. It’s effective at creeping me out, so I made sure to pick it up when I saw it at my local paperback trader.

The second influencing factor would be the book’s cover. And look at this thing. The skull on there frames all the little bits, which include some roses, and coins, ancient ruins, something strange and fanged lurking in a darkened cave. Spiders and sharp bits and smoke. The skull’s bald shine-spot could be a desert plain or a burning sun or a clouded maelstrom. It’s effective at creeping me out, so I made sure to pick it up when I saw it at my local paperback trader.

This book is actually a compilation of Martin’s earliest stories. As a short story compilation, all of these tales appeared in earlier publications. Most were in short story collections, which were more profuse in the 1970s and 1980s than today, though a few appeared in the magazines OMNI and Cosmos.

I’ll go over them one by one, hopefully in brief, but be aware: there’s a lot of horror in here. Lovecraftian-style ancient, lurking, eldritch horror, mixed into fantasy and science fiction flawlessly. There’s also a couple of dying earth tales, and at least one science fantasy, and a couple of interesting pure science fictions; the overall themes are horror, love, and loss. Martin got his start in television, working on the 1980s Twilight Zone, and these stories would fit into the Twilight Zone perfect. In fact, “Sandkings” itself became an episode of the revived Outer Limits (and, for the trivia-minded, also exists as a DC Science Fiction Graphic Novel). They’d also fit right in with Weird Tales, if it had still been around.

The Way of Cross and Dragon (OMNI, June 1979)

Our main character is a Knight Inquisitor for a starfaring inquisition, sent out to investigate a new heretical order following Saint Judas Iscariot, dragon-tamer and disciple of Christ. The order, as it turns out, is artificial: an order of Lies, as it were; the cult of Judas attempts to ensnare our Inquisitor, who’s harboring skepticism in secret. The plot is fairly straightforward, though it does raise questions of belief and faith, truth and lie, skepticism and security. Despite its brevity it is firmly thought-provoking, and delves into some deep questions about the nature of belief. Winner of the Hugo Award.

Bitterblooms (Cosmos, November 1977)

This tale starts off sounding very fantasy, but ends up with a weird science fiction/science fantasy angle. Protagonist Shawn went out in search of food and is now lost and alone on a dying world, freezing in the encroaching snow and pursued by hungry “vampires.” She bumps into a witch-woman named Morgan, who happens to live in a place untouched by the cold. Morgan’s ship can travel to other worlds—a nice nod to the other stories in this collection—and she posesses other strong magics. Shawn has faint reminders of her past, and begins to see Morgan’s illusions for what they really are. Again, very thought provoking in its handling of loss and love, with a powerful emotional core.

In the House of the Worm (The Ides of Tomorrow, 1976)

The longest tale in this book is another dying earth one, where humans have retreated into subterranean cities. Their decaying civilization is one of brutal nobility, surviving off the strange humanoid groun who live in the depths below them. Annlyn, our protagonist here, is slighted at a party by the Meatbringer, who then takes our hero’s girl; Annlyn rounds up his friends in a case of teenage bravado and takes off into the ruined tunnels to kill the guy. Things go badly for the group, and Annlyn ends up fleeing for his life into the darkness, deeper into the catacombs… to where the groun live.

The tale’s first half is very strong, with an evocative setting, and a brash, conceited, but likeable protagonist. The second half becomes a slow, methodical grind, moving from visceral into psychological horror. The ending brings things back up again, but the pacing staggers in the middle. Still, the decayed, dying world is superbly crafted—I can’t say enough praise about the setting—plus the protagonist has some real growth, and the end realization is both horrible and fascinating.

Fast-Friend (Faster than Light, 1976)

In the future, achieving faster-than-light travel is only possible by going through an evolutionary process: become a fast-friend. Protagonist Brand and his girlfriend both planned to go through with the change; girlfriend does, but Brand had second thoughts about losing his humanity, and balked at the last minute. Now, he floats around in space, miserable, alone with his angel—an organically-grown winged female sex-slave with a childlike innocence and bubbly personality. (Talking to his “angel” makes Brand sound like any ’40s Bogart character.) Brand doesn’t have any attachment to anything, though, and is losing what humanity he has left in his strange isolation; he’s focusing all of his intellect on his goal of capturing a fast-friend, harnessing it to his ship, and using its power to drag his ship at faster-than-light speed. You can only guess as to which fast-friend he captures; he does, of course, have a revelation at the end, and gets an ambiguous happy ending at least.

The Stone City (New Voices I, 1978)

A title like that should bring to mind Clark Ashton Smith or H.P. Lovecraft. (At least, it does for me.) The story is definitely a weird tale, with strong psychological themes of self-discovery and exploration. Holt is a member of a spaceship crew stranded on an alien world; the natives aren’t letting him leave, telling him to wait for the next outbound ship, of which there are none. The rest of his crew are either dead (from cultural differences with the natives) or have sunk into despondency. Holt is one of the two who retains some hope; he came here to study alien life, dammit, and this world happens to have ancient alien ruins. Which the ship’s captain entered, and never returned from. The ending is, again, more of a psychological twist than a proper horror revelation, but this is still very much a weird tale.

Starlady (Science Fiction Discoveries, 1976)

Another tale of people trapped on alien worlds; this time, it’s Janey Small, the Starlady, and her pal Golden Boy; they end up raped, robbed, and abandoned on another planet. Janey’s taken in by the pimp Hairy Hal (what names these guys have), an opportunist and perfect example of Martin’s detailed view of the dark side of humanity. Depending on your view of pimps, this is either shameful and insulting, or a sympathetic yet loathsome character. Starlady is pretty ambitious, and has a thirst for vengeance against her earlier oppressors, leaving us with an amoral shades-of-grey tale of prostitution and murder.

Sandkings (OMNI, August 1979)

The most famous of Martin’s stories, and rightfully so, the title story deals with Simon Kress, collector of rare and dangerous animals. By chance, he goes into the mysterious establishment of Wo and Shade, and buys the ultimate in dangerous alien pets: some sandkings. These small insects build their own castles in their special sandbox, fighting endless wars after building up their strength; their castles are covered in depictions of their god… Simon Kress. Kress, of course, mishandles them to make them meaner and nastier, and then runs sandking fights to entertain his friends, throwing in other animals to make things interesting.

Kress’s girlfriend takes umbrage at this, and reports him to the animal control authorities; he feeds the sandkings a puppy and sends it to her on video. She returns to his house with a sledgehammer, and bashes in the sandkings’ glass sandbox, freeing them. In a panic, Kress flees; he returns the next day with a batch of hired assassins, finding the sandkings grown to enormous size without the constraints of their original habitat. The situation continues to spiral out of control, leading to a horrific ending. It’s a perfect horror story: a dangerous alien race, the failed attempt at playing God. Another Hugo Award winner.

The Bottom Line

“Sandkings” is probably the best and most famous story in this compilation, and for good reason: it’s superbly written, pretty damn horrifying, and has strong lasting power. It’s a toss-up between it and “In The House of the Worm” over which is my favorite story; “Sandkings” is the better story, in terms of pacing and plot, but for me “Worm” has more horror, I really dig its Dying Earth world, and it stuck with me more than any of the others. I lean towards “Worm” for favorite, but it can’t beat “Sandkings” as the best. “Stone City” is also really good, being a love-child of Ace Doubles and Lovecraft; “Cross and Dragon” is an interesting analysis of belief.

As for the weak points… “Starlady” comes to mind. While it isn’t a bad story, it is anti-climactic, and felt flat in comparison. Plus it doesn’t fit in as well with the others. The closest would be “Bitterblooms,” with which it shares themes of love and loss. I’m on the edge about “Bitterblooms;” it lacks the insight of “Cross and Dragon” and the visceral horror of “Sandkings” or “Stone City,” though it is a good psychological tale. It’s also the one that generates the most emotional response, so while I don’t think it’s as developed as the others, it is a powerful tale. “Fast-Friend” is another I’m on the fence over; it’s not a bad story, with an interesting world and good pacing, but it is the most predictable and bland story in the book. Still, “Starlady” is the only one I wasn’t thrilled by; the other two have weaknesses, yes, but quite a number of merits.

This collection surprised me by its strength; the horror tales are superb in their visceral spine-chilling, the psychological tales are great at making you think, all of them are amazing for the depth and creativity for their respective settings. Martin’s prose isn’t the same as his Song of Ice and Fire stuff, but it is just as tight, and even more effective; fascinating to think that the man went from writing tight, thought-provoking short stories to one of the longest fantasy series in print today. I guess I shouldn’t be surprised that Sandkings is one of the strongest short-story compilations in my collection.

These tales are quite accessible. The original Baen Books copy is still around in many used book stores, the Amazon Marketplace, and eBay. Most of the stories have been reprinted in ebook forms, if you’re going electronic or are on a budget. “Starlady” and “Fast-Friend” were reprinted by Subterranean Press in 2008 in an Ace-style double hardcover for $20; these were some of the weaker stories in my opinion, though it’s nice to see doubles again. And its cover is pretty slick.

Great site. Love your comments. TNKS

LikeLike

I absolutely loved the story “Sandkings,” which I first encountered in one of the Hugo Winners volumes (the ones with Asimov’s introductions). While I’m not a huge Martin fan, or at least don’t particularly care for A Song of Ice and Fire and its like. But Sandkings! Wow, what a wonderful story. I enjoyed your review, and it reminded me just how good the story is. How it’s avoided being made into a movie is beyond me.

LikeLike

I was just talking to one of my friends, and found out he put the story “Sandkings” as one of his top three science-fiction picks. I’m not sure I’d put it in my top three overall, but it is one of the best short-stories ever written.

Sadly I think it’s been forgotten, considering it had that Outer Limits episode and graphic novel in the ’80s when it was new(er), because it would make an amazing movie.

Thanks for the comments! (Nice blog by the way.)

LikeLike

It’s always great when someone criticizes any authors writing skills and then has mistakes in that very same critique. Right in the beginning, “Including George R.R. Martin.” is not a sentence. Writing, “…authors, including George R.R. Martin.” would have been correct. Then in the following paragraph, “…even if it is the horrible long-running, never-ending megaseries…” should have either been “…horribLY long-running…” or “…horrible, long-running…” (Notice the comma) depending on what you were trying to say.

Don’t feel bad though, a lot of people had rough time with highschool grammar. Remembering what an adverb is is so hard!

(I wrote this on an iPhone on the toilet, so pardon me if there are any typos of my own)

LikeLike

Excuse me, that should read, “…author’s writing skills…” Again, I’m on my iPhone taking a dump.

LikeLike

Pingback: 3 Year Anniversary | Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased