Tags

1970s, 1979, apocalyptic, Cold War, colonization, dystopian, first contact, Frederik Pohl, Gollancz SF Masterworks, Hugo Award nominee, Locus Award nominee, National Book Award winner, Nebula Award nominee, postcolonial, science fiction, utopian

It is worth mentioning, early and often, that Jem the novel is unrelated to Jem the 1980s cartoon show and doll brand.

Frederik Pohl is one of the many legends of the Golden Age of Science Fiction; while he was a prolific writer of short stories and novels, his greatest accomplishment was editing more science fiction digests than anyone else. While he left less of an impact on the genre than John Campbell, he was the lead editor for Astonishing Stories, Super Science Stories, the mighty Galaxy in its heyday, and Galaxy‘s little experimental brother If, a magazine Pohl turned into one of the best professional magazines in the late 1960s. Pohl knew a good story when he saw one, and whatever else you can say about the man, his work on the post-war digest magazine field was a credit to science fiction. But he didn’t stop there; he also knew how to pen a good short story, and has a number of popular novels, including Jem.

The works by Pohl that I’m most familiar with are his short stories — “The Tunnel Under the World” is a solid tale in the Dickian vein, and one of my favorite Golden Age shorts — and his novels Chernobyl, The Space Merchents with C.M. Kornbluth, and the Starchild trilogy with Jack Williamson (reviews forthcoming). Jem caught my eye at a local library bag sale; all I knew was that it was one of the last novel serialized in Galaxy before it collapsed—a serial run that took the space of, as I recall, three years, well after it had appeared in book form—and that it frequently crops up on many Best-Of lists.

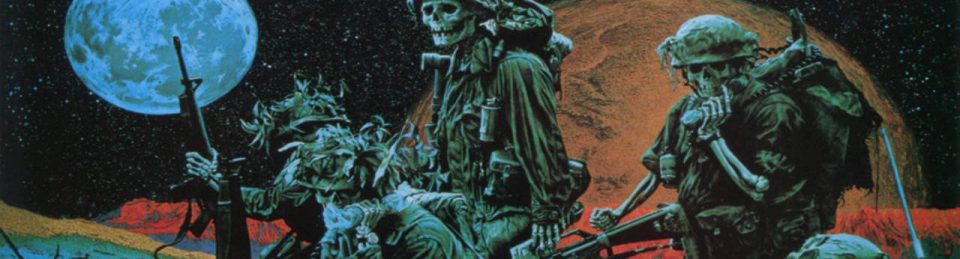

First off, the cover. Normally I’d rather do the cover closer to the end, but this one is so godawful that we’re dealing with it first. Big block letters, dull red-brown background, plain white text. I guess it’s a way to cut costs, but for a science fiction novel, this cover is painful, possibly the blandest cover I’ve ever seen. It isn’t very endearing; my best guess is it’s trying to replicate the color of the planet, dull mud earth-tones and the thin red light from its star.

The background is pretty important to the story, so let’s get that out of the way. Earth is divided amongst three power blocs: the Food Bloc (aka the Fats), the food-producing nations which includes the US and Soviet Union; the Fuel Bloc (aka the Greasies), which would be OPEC and the UK, which discovered oil off the coast of Scotland; and the People Bloc (aka the Peeps), which is China, India, Pakistan, and most of the third world. While they do live in a world of globalized mutual interdependence, they’re also part of a grandiose Orwellian power system, with each bloc at odds with the others under the surface, but dependent on the others’ food, fuel, or human resources. It’s an imaginative future; written in the Cold War, it’s interesting to see this future Cold War, but also somewhat odd to see the US and USSR allied in the same bloc.

The story begins when a Pakistani scientist (People Bloc) reveals the discovery of a habitable, Earth-like planet: the first such planet ever discovered. Billed as a possible utopia, the three blocs struggle to get their own scientific team together to explore (and occupy) this new world. The People Bloc gets there first, but undergoes calamity after calamity. The Food Bloc shows up next, and things go fairly smoothly for them. Last but not least, the Fuel Bloc arrives, being the only bloc which can afford to send vehicles and air conditioners along. Pretty soon sentient native life is discovered. Also, at some point everybody decides to call the planet Jem for some reason, even though its official designation is Geminorum 8462. It’s also revealed that the sun it orbits isn’t nearly as bright as Earth’s Sol, producing more solar radiation than thin red light.

Each bloc sets up shop next to one of Jem’s three native lifeforms, all of them sentient but primitive: the Peeps are attacked by melted crabroaches who communicate telepathically and see via echolocation; Food lands next to a group of floating monkey balloonists; and Fuel makes contact with a group of subterranean dog-sized rats. All of these are perfect examples of Campbell’s decree: “show me a creature that thinks as well as a man, or better, but not like a man.” They all have complex and unique societies, but their thoughts don’t resemble human society in the slightest. In a way, it’s something of a tale of Post-Colonialist science-fiction in what happens.

My biggest flaw with the book is that almost every character is so goddamn unlikable; there’s the arch-conservative who combines the worst aspects of the Daddy’s Little Girl and Army Brat/General’s Daughter stereotypes; there’s the many scheming Peeps and Greasies to counter the Heinleinian conservatives who run the Fats; and most of the Food Bloc’s expedition members are either morons, frat-boys, or a right bitch. One guy starts shooting “specimens” of the native life as soon as contact is made, and despite reprimands from his bitchy team leader, he continues; she becomes even more of a right bitch when her team stop paying any attention to her and just do whatever the hell they want.

I ended up feeling more sympathy for the native species from how badly they’re abused. They don’t know any better, but love to help out the Earthlings; for example, the Balloonists are glad to make some new friends, but end up screwing themselves over by not migrating. The natives are treated as nothing more than potential customers and market-shares before they become weaponized spies to further the warfare between the blocs. Nobody really cares about their well-being; they’re just another resource to expend. For example:

For openers, Dr. Ravenel, I’d like to see your people create some trade goods. For all three races. They’re all going to be our customers one of these days.

There are three people—the main characters and a sidekick—who I actually felt sympathy for, because they weren’t total assholes. (That said, two of them were painfully naive, and the third was a Space Russian pilot, and what kind of horrible person hates a Space Russian?) Our protagonist is Danny Dalehouse, professor at Michigan State University (go Spartans!) and physicist extraordinaire, who starts off at the lecture where Jem (the planet) is revealed. He’s a member of the Food Bloc expedition, and ends up being the only level-headed person in it; he’s just a civilian scientist, though, so he doesn’t do very much. The other would be Ama Dimitrova, Bulgarian and on-off girlfriend to the Pakistani scientist, surgically altered to become smarter, which leaves her with crippling migraines, the ability to show human emotion (hey, it’s rare in this book), and mind-boggling amounts of naiveté. Thick as they are, these are our two heroes: the people with their hearts in the right places, even if their minds are sluggish for being such geniuses.

Oh. Things heat up and become even more of a Cold War allegory when the three Blocs go to war on Earth, destroying everything, and stranding the three groups of assholes on Jem without any resupply.

I don’t want to spoil the ending by bitching about it—that said, I didn’t like it—but there is one more thing I’d like to grouse upon. The novel is on the fence about blending satire and Orwellian serious commentary; this isn’t a bad thing, until Pohl for some reason decided to work in a bizarre “free love,” “lotsa sex” subplot. (I worry that it was his attempt to reflect on contemporary society.) The ape-like balloonists reproduce by firing their seed into the wind, which lets solar rays hit it before it meets the ova; thus, life not by evolution but by radiation rays. The Fats learn that this can be triggered by flashing light; the unforeseen consequence is that it’s an aphrodisiac for humans, and leads to at least one poor little balloon bastard being captured and used as a date-rape drug. Even more unforeseen, and another reason why I say it’s a novel on the horrors of Imperialism taken to the stars, is that the balloonists can’t reproduce without specific solar flares, so they’re crippling the balloonist race by forcing them to wank off constantly. Congratulations, Pohl, you managed to hit something that’s creepy, idiotic, and pitiable all at once.

Is Jem a great novel? The National Book Foundation seemed to think so, since it got a National Book Award in 1980. Pohl really outdid himself in terms of complexity, political depth, and world-building; he really shines at all of these, and they are Jem‘s strongest point. This is not a light, throw-away Pohl novel like the others I’ve read, this is a sweeping vision on a massive scale, filled with reflections of the contemporary socio-political tapestry. I also have to say that it kept me wanting to read more; it’s the kind of book that tosses out fascinating ideas and events frequently, interesting enough so you’ll want to see how they pan out.

That said, I came away disappointed with Jem, and several times I came close to giving up on it. When the book hooked me and kept me reading, it’d do something in the next chapter to disappoint or frustrate. The cast of characters is an object lesson in creating assholes; this is more a damning indictment of human nature than it is a novel about exploring another world. (Which, in all honesty, is precisely what good science fiction does: review and reflect on the current world in such a way that the reader stops to think about it.) Jem is a book that I seriously wanted to like, but one with terrible flaws. So many, many flaws. I can’t actually recommend this book unless you’re a big fan of utopian literature, if you like hating most of the characters, or if you like your SF to be a heavily philosophical indictment of humanity.

Much like with A Door Into Summer, I’m not sure why this book still graces so many “best SF books” lists. Door I can somewhat understand; it was a capable early time-travel novel, even if it lacks complexity and has since become the cliche. Jem, on the other hand, is a great concept with a muddled execution. It’s a powerful and complex work, with a lot of strengths that should be commended, and a lot of weaknesses that made me want to pull my hair out.

I come away disappointed with most of Pohl’s works as well (for example, not at all a fan of Gateway or its sequels). I looked through the entire publication history of Jem and their covers and realized that they’re all terrible — alas. This is the exact copy I have as well – it’s not high on my list to read.

LikeLike

I really, really wanted to like this book—Pohl crafts a very complex socio-political-philosophical work here—but it’s too flawed to work right. There were times where I was about to put it down, and a chapter ended on an interesting note; I’d read some more the next day, and be horribly disappointed. So I ended up really, really hating it instead. Another bad choice in reading material this summer. Between “Jem” and Philip Jose Farmer’s “The Dark Design,” I almost gave up completely on trying to read ’70s science fiction. I didn’t, and the 1970s were somewhat redeemed in my eyes, in yet another review coming down the pike.

It’s a bad sign when even the SF Masterworks cover looks like crap, which is of our protagonist Danny Dalehouse and the simian balloonists. (At least, I remember them being described as simian. On the cover, they’re like floating mushrooms.)

LikeLike

Shudder — The Dark Design — after I read that piece of tripe I’ve refused to read any of Farmer’s other works — but I also hated To You Scattered Bodies Go…

The 70s are great! But yeah, not Jem or The Dark Design.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Disagree. There are very interesting works that came out during this decade. I enjoyed Scattered and JEM and would recommend them highly. Man Plus by Pohl can easily be a movie. Loved that book… Good 70´s Sci fi? Flow my Tears by PKD, Rama by Arthur C Carke, The Forever War…

LikeLike

Disagree that Riverworld was an atrocious train-wreck of leaden prose and rape? Well, I’m glad someone found it enjoyable even if I didn’t.

I’m actually curious about JEM, what were your favorite parts of the novel? What earned the high recommendation? I ask because I see a lot of potential in its core concepts, but found the execution very ham-handed… it had good potential as a social satire paralleling the Cold War power blocs abusing natives for their own gain, but Pohl forced it too much compared to his most successful satires (The Space Merchants coming to mind).

LikeLike

“No survivors, only replacements.”

LikeLike