Tags

1950s, C.L. Moore, dystopian, memory, psychological, Richard Powers, Ruth Ray, science fiction, totalitarian state

Something’s eating you,” I said. “Anybody can see that. Maybe I should have started off with, ‘Tell me, good Brutus, can you see your face?’ It’s obvious.”

He rubbed a hand over his face and looked at it vacantly, as if he hoped the expression would have come off so he could inspect it on his palm, like dirt.

Catherine Lucille Moore was the first major female author writing speculative fiction in the 1930s; her career blossomed through the 1940s and 1950s, until she stopped writing in 1957, the year before her husband (and fellow SF writer) Henry Kuttner passed away. While they each wrote on their own, collaborations became the norm after their marriage; together, wrote a huge body of stories for Astounding Science Fiction during the war years, carrying the magazine while other authors were doing government work. Her second husband forbade her from writing genre fiction; a damn shame; a crime even. It makes me wonder just how many great novels Kuttner and Moore never got to write.

This book—Doomsday Morning—was her last solo outing, back in 1957. It’s unique, standing out in her bibliography one of the few true science fiction works she wrote, and not a Burroughs-style science fantasy or a Lovecraft-inspired weird tale. And it’s a dystopian novel with themes revolving around theater and state control. Not your ordinary science fiction novel.

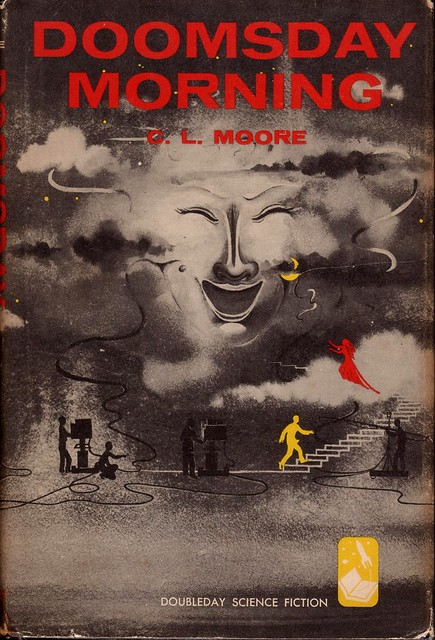

Doubleday – 1957 – illo by Ruth Ray. A simplistic cover more about television than theater. Very old-school.

Following the Five-Day-War near the end of the 20th Century, the United States finds itself under the watchful eyes of Comus (short for COMmunications U.S.) and its benevolent dictator, President Raleigh. Not only does Comus control the communications network, it’s also the Orwellian authoritarian state which makes the trains run on time and ensures each laborer is provided with daily food and provisions… at the cost of those various personal freedoms. After several decades, memory of life without Comus’ eternal oversight is nonexistent, though President Raleigh is growing quite old—and people fear the succeeding dictator won’t be as benevolent.

Howard Rohan (no relation) used to work for Comus (no relation), as a brilliant actor, director, and screenwriter. Co-starring with his wife Miranda, their films became quite popular, and the couple gained wealth and prestige. Miranda’s death haunted Rohan, who (like most male protagonists in this situation) blamed himself for her death, assuming his inattentiveness was the reason for her demise. As Doomsday Morning begins, Rohan’s a Cropper, a futuristic version of Steinbeck’s migrant worker Oakies from The Grapes of Wrath, an angry, depressive drunk hiding from his past at the bottom of a barrel.

Then, Rohan’s life undergoes irrevocable changes. Comus wants his theatrical expertise to help them out of a bind. Something’s stirring in California, where Comus has receded for some reason, and Rohan’s old acquaintances want him to bring Comus back into this barren land as part of a roving theater troupe. Things aren’t adding up to Rohan; why him, why now? How bad are things in California? And more pressing, why are references and predictions from one foggy dream coming true?—probably, Mr. Rohan, because that was no dream. Thrust between Comus and open rebellion, Rohan is put in the role of leading man in a new Comus-authored play, and that of a wary spy in the real world.

I’m always interested to see how things like governance, freedoms, and social control operates within dystopic/utopic fiction, and Doomsday Morning is a gold mine. Given its place in time—post-McCarthyism, and just before the launch of Sputnik—the novel has clear allusions to Soviet Communism and the Axis dictatorships. It’s also worth noting World War II was the last gasp of one-man rule in Europe; monarchies were on the way out, and fascism had lost any of the charm it might have had in the 1930s. Meanwhile, the West was working overtime to prop up dictators such as Batista, Trujillo, and the Shah of Iran to fend off Communism, so not all dictators were portrayed as Bad Men. Thus the novel is a lot more complex than a simple allegory for Stalinism; at one point, someone notes that President Raleigh doesn’t want to die knowing he was the man who’d turned America into a dictatorship.

And we never get a clear picture of this new America, of day-to-day life under the dictatorship. We see a bus taking impoverished Croppers into Indiana—sounds like more of a critique of robber-baron capitalism to me, with laborers trapped into the life of servitude to large corporations—and a burnt-out, shattered California, mangled not by rebels but by looters—former Comus men, disillusioned rebels, and escaped prisoners. I would have liked a larger picture of this world, and to have known more about the Five Days’ War and the birth of an American dictatorship, but I’m also glad Moore kept this information secret. That’s not the point of the story; Rohan and his decisions are, since he ends up with the potential to alter the world.

One of the general complaints about C.L. Moore’s writing is that more often then not, things happen to her protagonists, instead of the protagonists moving things forward. That’s been true for what I’ve read, the Northwest John Smith and Jirel of Joiry stories. And while there’s a bit of that in Doomsday Morning, Rohan is more assertive, driving the action forward and interacting with the setting. Although, much of the novel takes place in Rohan’s head. It’s introspective and psychological, with Rohan pondering everything, always drawn back to the memory of his lost wife. Rohan’s personal complexities enhance this heavily internalized first-person PoV, though some of his choices felt unnatural—the third act starts with Rohan coming to grips with his wife’s death, and this becomes incentive to choose a side in the conflict, which didn’t feel like a logical choice.

Between that slow introspection and a more science fiction-y focus than Moore’s standard fare, Doomsday Morning is different from her earlier works. There are some intense action sequences that manage to intrude upon a novel about governance and theater, without feeling unnatural or rushed, and they’re damn good action sequences to read. The prose in, say, her Northwest Smith stories was lush and lurid, dripping with exotic scenery and visceral imagery. Doomsday Morning has beautiful prose, though it’s comparatively subdued, depicting the great Redwood forests of California instead of a Mars that never was. It has more of a pastoral Americana feel—similar to Simak’s City, or Brackett’s The Long Tomorrow—while retaining her beautiful imagery and smooth, compelling prose. If you’re not put off by heavy introspection—I wasn’t—the book makes for smooth and pleasant reading.

I ended up liking Doomsday Morning despite its eccentricities: the pacing is subdued, introspective, and sluggish; the setting isn’t as well defined as it could be; many of the protagonist’s decisions didn’t make sense—some parts of the plot just happen. But you know what? It was a good book and a great read. Rohan’s a complex protagonist in the process of developing, three-dimensional and sympathetic, which makes his musings enjoyable. What we see of the setting is amazing, a glimpse into an alien America. The action scenes are tense and well-depicted; the introspection fluid and fascinating when it’s most relevant. The plot meanders across the tranquility of pastoral Americana before heading into an unexpected finale bristling with excitement. And Moore’s smooth and compelling prose made up for the sluggishness. Not a perfect book, but I’ll still recommend it to any science fiction fan.

For another opinion, check out the review at SF Ruminations.

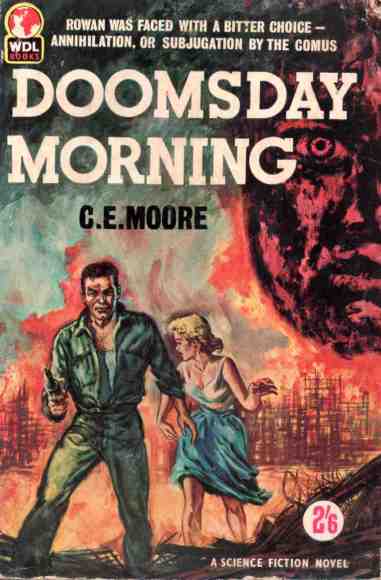

Great review as always. I have the first edition but desperately want the Powers cover! He’s almost always brilliant! I’ve tried to read the book at least three times but the “sluggishness” always gets to me — I rarely get more than 25 pages or so in. But I should definitely give it another shot….

LikeLike

It does start off pretty slow, and to be honest it never really gets up to speed, especially compared to Moore’s usual fare—what it considers “fast,” other books consider third gear.

Still recommend it though, it’s got a lot going for it if you can get into its slow, methodical, but engaging groove.

LikeLike

Tangent: Have you read Judith Merril’s Shadow on the Hearth (1950)? Another pulp writer (as you know of couse — hehe) who sat down and tried to write a more serious/slow work of sci-fi distinctly different than the normal pulp of the era — I’ve been contemplating buying a copy.

LikeLike

Haven’t actually picked up anything Merril wrote — but that one is on my buy list, because of its post-apocalyptic nature.

LikeLike

Pingback: Doomsday Morning, CL Moore « SF Mistressworks

Pingback: My Eight Additions to SF Masterworks | Battered, Tattered, Yellowed, & Creased